The predictions for next year are coming thick and fast; the trend reports and action statements. Next year will be the year we come together to solve climate change. Put it on the kanban board! I’m likely going to be in hospital in a few days for a little while more so already have an end of year post deep in drafts and am making the most of my recognisance to do little bits of reading now. For now I want to pick up this preferable futures thread…

An argument for dread

A couple of years ago I was at an event in Geneva, there to talk about something or other. Julian Oliver was up before me and as opposed to previous times where we’ve been on stage together and talked about technology and critical practice, he launched into a brutally unrelenting and damning litany detailing the state of the planet and the despair he felt – maybe a solid 90 minutes of horror. This was just as he turned his life towards climate related work and support XR with their infrastructure. The anger and despair he felt energised him to get up and use his skills to do something.

I also left that talk changed, shortly after I stopped eating meat and changed the way I consumed stuff. It’s not like I was ignorant of climate collapse before, but the sheer dread I experienced of having the near-future state of Earth laid out so clearly drove me to anger and to action and to really question and change little every day actions as well as do a lot more where I could in my work. The effect of this dread was that it made climate change less abstract and alien and more material and real.

Later, I invited Julian to come and give the same talk at any away day at the university I worked at and the same thing happened; several colleagues told me it had changed the way they lived and worked. Shortly after, when we looked at how to embed the climate emergency in teaching, people were seized with an almost zeal about it. I don’t know how much Julian’s perspective influenced that zeal but I’m sure it did in some small part – at least two folks told me so.

This is why the push back on dark futures and ‘dystopia’ makes me a little uncomfortable: Anger and outrage are powerful tools for action; it’s what the right-wing has been using for the last few years to stoke extremism and inflate their power. It’s what protest movements like XR, Just Stop Oil and Tyre Extinguishers have been using to drum up support and controversy; an intentional tactic to keep their issues at the centre of public discourse. But the last few years of design and futures discourse has seen a push back against it to be replaced with hopeful narratives and ‘preferable’ futures.

I’m absolutely not dismissing the value of positive future imaginaries, even ‘preferable’ ones within their limited frame of reference. I agree with the thesis that negative stories can be overwhelming and paralysing, making you feel helpless. Others argue that we are already suffused with grim stories of dystopian (or dark*) futures, particularly through science fiction and that they just drive us to despair. Equally, that the things we may think of as dark futures for northern Europeans are the lived experiences of people in other parts of the world we are aestheticising for the sake of some high-minded discourse.

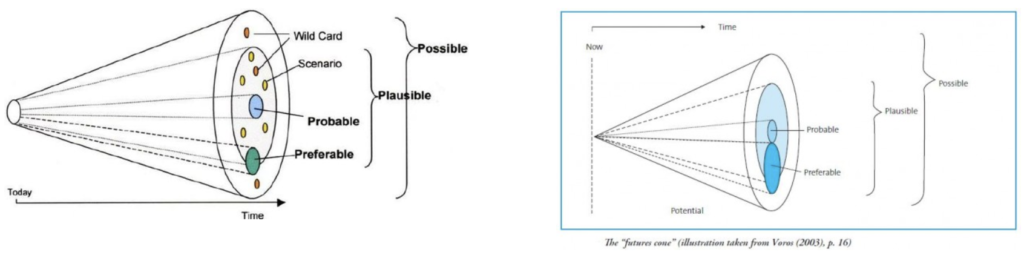

Remember that the point of speculative practice is not about making predictions or even defining preferable futures but in mapping out the space of possibility so that we can think critically about the choices we make today. There’s a lot of nuance here but fundamentally, if we diminish the ability to confront the ‘bad’ outcomes then we also diminish their presence in the mind of people and provide a cover for inaction in hope: A focus on the preferable future, erases, forecloses or precludes other possibilities.

The point of speculation is to bring out and materialise many futures and hold them together to navigate and negotiate them without precluding or proscribing and particular ones based on preferability.

Studies have shown that optimism and hope can lead to inaction, it even appears in historic political phenomena such as Sebastianism; the Portuguese myth of the king returning to elad the country back to some made-up greatness. A good balance may be found in the Stockdale paradox – the ability to both hope for the better as well as totally engage with the facts on the ground with no sense of escapism. But this means acknowledging, talking about and describing the potential grimness of things to come to make different choices today.

As Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams wrote ‘You can’t resist new worlds into being.‘ Where left-wing/liberal/green protest movement can be very good at identifying, targeting and challenging the object of antagonism through a dark vision of what is to come, they aren’t very good at proposing what comes next; what does the world where XR win actually look like? What’s the pay-off? Yes, it would be ‘better’ but how? It is arguable (and is regrettably, compellingly argued), that the world right now is pretty good if, for instance, you’re a wealthy human being in a European capital. The conservatives are very good at this because the world they want to build is the world of recent fictional nostalgia; where you didn’t have to worry about immigration, or climate change, or gender, or sexuality, or new drugs, or fat cat financiers, or the cost of living. It’s a world in which you get exactly what you want and you live worry free. That’s a compelling sell as preferable futures go: Q is a preferable futures project; Brexit is a preferable futures project.

I refer back to Occupy a lot, it was – before being torn apart by infighting – the smartest and most brilliant protest movement. It very clearly identified what it was angry about through Graeber’s brilliant slogan ‘We are the 99%’, it proposed the solution – deliberative democracy – and made it real by bringing it into practice at the actual Occupy sites. It was a movement motivated by fury that used that fury to bring a new world into being.

*I think about ‘dystopia’ as a an absolute category; it’s not meant to be read as anything but fantasy while ‘dark’ futures are at least plausible. Monika’s work on Protopia futures is critical here because it dismantles the whole hated utopia/dystopia division in the first place. (I think we can, as a whole, dismiss utopias and dystopias as co-dependent fantasises that only work as a form of escapism.)

Short Stuff

- Last week, Stackoverflow had to stop taking answers from ChatGPT following responses flooding the platform. The answers can look really plausible but are often incorrect. It exposes a problem with these types of services that can easily fall prey to large language models (LLMs) and straight away made me imagine a future of roving LLMs holding websites hostage in exchange for training data. I think this is really interesting signal which indicates a new form of interaction or attack. Similar to how everyone was unprepared for DDOS’ a few years ago. Content bombing.

- Or ‘fiction as malware‘ for disabling/revealing AI systems.

- David Karpf celebrates a sign that Apple might be returning to realising that people just want things that improve their lives, not abstract techno-fantasies.

- Nuclear fusion breakthrough. (Since I put this here, it went from interesting to small announcement to FUSION IS COMING! on every news channel to ‘no it isn’t’ again in a few hours. Interesting to compare it to block chain coverage because, you know, it’s actually useful.)

- More on the failure of voice assistants.

Ok, love you very much as well you know.