This is a rough, edited transcript of the talk I gave for Bartlett Cinematic and Videogame Architecture students on Monday. I recorded it on my phone which was sat next to me and then used Otter.ai (which is very good I think) to transcribe. Back in the day everyone used to blog their talks and I really liked it so I’m going to try and get back into the habit. I should note that for these types of things I rarely really properly ‘prepare.’ I tend to thrown some ideas together that I think/believe will chime with the audience and then have a more discursive meander through those ideas with them. With more professional stuff it tends to be a bit more uni-directional and pro. Also I don’t have time to scroll through for all the typos and you know I’m bad at that anyway so just apologies in advance really. Anyway, transmission begins:::

Hi folks, thanks for having me. I have to say I’m pretty jealous, if this course existed ten years ago, I would have done it. So I’m going to talk about this idea called ‘Design in the Construction of Imaginaries.’ And I choose these words, for a particular reason, I’ll come on to how I’m gonna use them in a way in a second. But I think it’s important to be on the same page here about what these words mean.

So I come from a design background and I’ve taught interaction design and graphic design and product design and UX and all sorts of stuff. But when I talk about design, I really just mean a sort of sophisticated understanding of material culture. So that might mean digital stuff, it can be physical stuff, architecture. And design means thinking about a particular affect or effect that you want to have on the world. Whereas (and this is purely my own definition) art I think is more subjective, it’s about you as a person.

So then imaginaries is an idea from social science, Sheila Jasanoff is probably the person to read if you’re interested. Imaginaries are a sort of collective headcanon for things in the world. So we have an imaginary of artificial intelligence, which I’m going to talk about quite a bit. We have an imaginary called London, we have an imaginary called gender, we have an imaginary of ‘our people,’ nations have imaginaries. So these are all sort of constructs of certain tropes and myths and stories and visions that we all collectively hold and often can be quite tricky to pin down. And I’m very interested in how design constructs imaginaries, both to build and reinforce mainstream imaginaries but also; how can we use design or material practice that to unpick these imaginaries as well, to challenge them, to question them and to sort of disassemble them and show their parts which is what this little talk is all about.

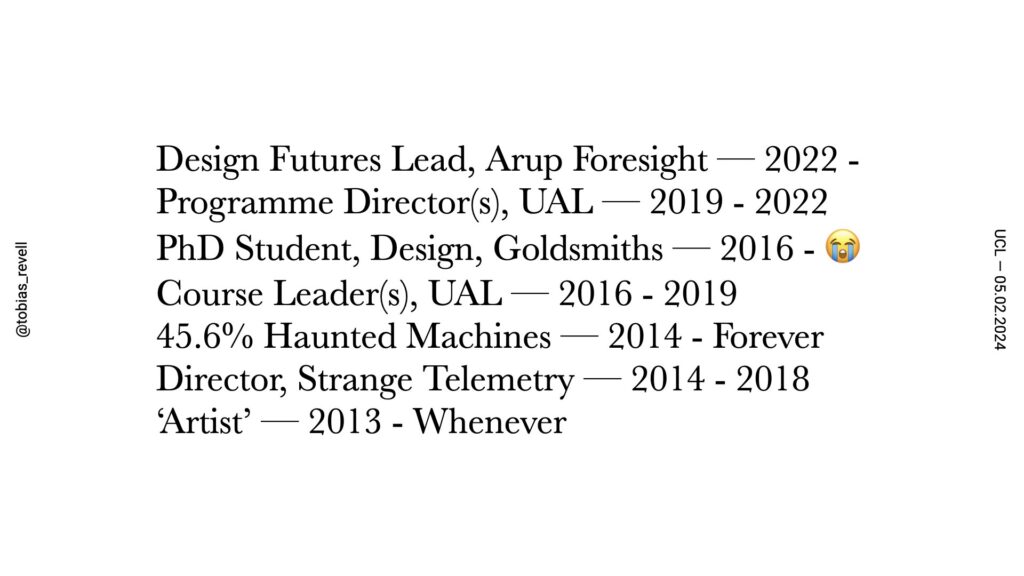

So very quickly who I am and what I do. I’m Design Futures Lead at Arup Foresight. My job is to think about what the future of various things and for the sake of Arup and our clients, but particularly I lead on using design methods to do that and we have a small growing design team who use design to both produce certain types of outputs like exhibitions and films, but also as a research technique. Before that, I was an academic for a long time and I also ran a curatorial and research project called Haunted Machines with Natalie Kane. But a lot of what I’m going to talk about is mostly related to my PhD work, which I’m doing at Goldsmiths.

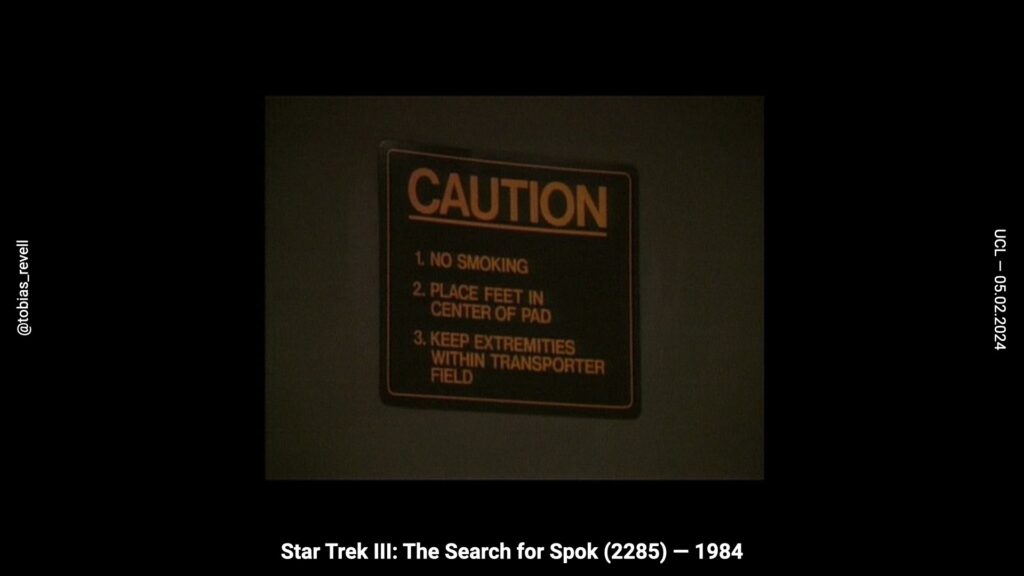

So I’m going to kick off with this with with a concept called future foreclosure. This is the idea that we’re not very good at thinking about the future and actually, the futures we construct and the futures we imagine are actually quite limited, and increasingly so. This shot is from Star Trek III; The Search for Spock, which is not as well studied perhaps as 2001; A Space Odyssey for its set design. But still, Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek put a lot of effort into designing the detail around the Starship Enterprise, including this sign on the transporter, which says ‘No Smoking.’ And I love this because it indicates a world in which the people of the 1980s were able to imagine a future in which you could dematerialise and rematerialise somewhere else completely through this amazing technology. You could jump from a spaceship to a planet or a ship to another ship but, everyone would still be smoking. It shows how we don’t question accepted social norms.

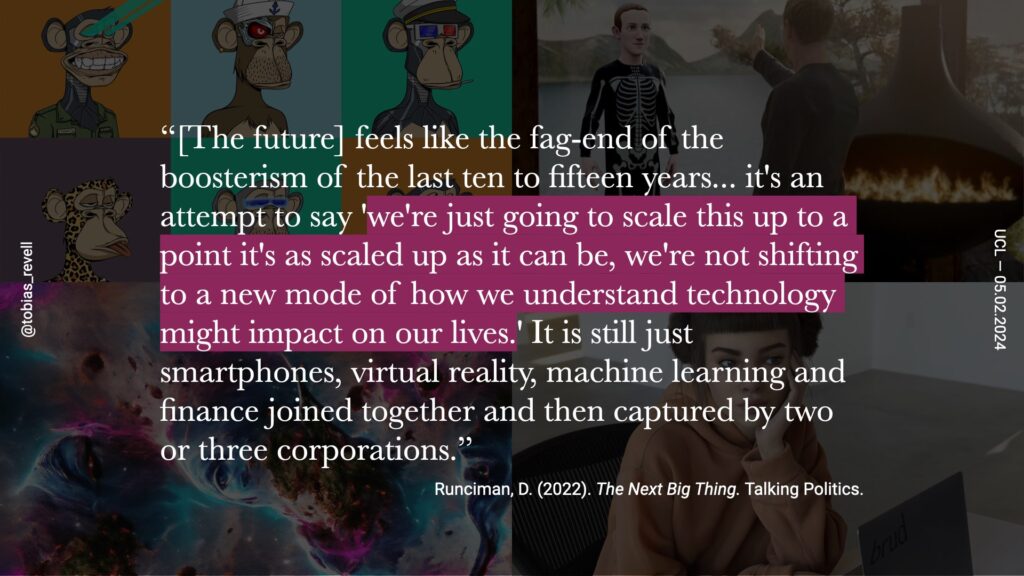

And then there’s this idea that we’re in a kind of bleak place for the future. This is a quote from David Runciman, who’s a Cambridge political scientist. And he was reflecting I think, on what happened in 2022. And he said…

We were talking about the metaverse earlier as perhaps one of the greatest examples of that. It’s just bootstrapping technology onto a financial instrument, and hoping for the best. So there’s a sort of cynical lack of imagination about what the future might be but also a sense of inevitability. My research looks at how AI has been socially constructed, and design’s role in that. One of the really fascinating things about AI is that everyone has a concept of it. Everyone’s seen films, video games, everybody’s heard hysterical news stories. But that also creates its own problems, because it gives AI this sense of inevitability. So these scholars reviewed I think 200-odd ethics guidelines for the use of AI across governments, nonprofits and companies and said…

So that imaginary of an inevitable AI coming is so secured that all of the discourse is just about limiting harms. And this percieved inevitability; the idea that nothing can stop the status-quo AI future and no alternatives can be imagined blinds us to the harms. Sun-ha Hong talks about the idea that…

So there’s this idea that a techno-future is inevitable and foreclosed but it wasn’t always so right? There were times where we’ve had alternative visions for what technology could be. Anyone seen David Cronenberg’s Existenz?

[Group of Gen Z’s doggedly keep their hands down] Oh boy. Okay. So this came out of this same year as The Matrix, 1999. And The Matrix obviously has become a real hallmark of what people now think about as a retro future; the idea of immersing ourselves in a simulated reality and an artificial intelligence that takes over. But Existenz was looking at the idea that we might be carrying around these bio computers or ‘pods’ that we plug into and exist in a different sort of virtual reality that existed between these bio pod. At the time, that was another future imaginary that people had and yet for some reason this is now seen as unreasonable and ridiculous while The Matrix is often held up by journalists as a potential future reality.

So, why do some imaginaries, like an AI apocalypse in The Matrix, take hold and others don’t and what role does design have in the success or failure of them?

Minority Report by Steven Spielberg came out a few years later in 2001. It’s a hugely influential film on the world of design and technology for reasons I will go into in a second. And it’s a really interesting case study in the cultural impact of one film over a huge collective imaginary of what technological futures are. Minority Report (based on the Phillip K Dick short story of the same name) takes place in a future where we’re able to predict crime before it happens and so there’s a ‘pre-crime unit’ that arrest people before they commit the crime. But there lots of other technologies in it like a gestural interface thing, augmented reality, eye tracking, AR and facial recognition. Almost all these technologies that were speculative at the time, captured here.

And so Minority Report becomes a powerful comparison point for journalists and investors around technology for years to come. Rather than opening us to alternatives or presenting a critical question, Minority Report is used as a story, a metaphor of a particular technofuture that drives billions of dollars of investment to technologies like gestural interfaces, AI and worst, predictive policing.

We might think that the role of science fiction, fiction and cinema is to broaden our future imaginaries and to help us challenge the status quo rather than but as philosopher Fredric Jameson said…

Jameson makes a really interesting suggestion that really the role of futures in science fiction, in most cases, isn’t to broaden our imagination, and throw in new ideas and new questions but is to convince us that we’re just in the past of a future that’s inevitable and already pre-decided.

Minority Report becomes incredibly influential. It has a whole Wikipedia page dedicated just to the technologies that are that are in Minority Report. The production team work with loads of researchers at places like MIT and all sorts of technology companies to develop these gadgets and gizmos. And then for years and years and years. We’re talking over two decades now, people have been trying to recreate the technology in Minority Report or using it as a metaphor – a framing device – for real-world technologies.

But there’s a very good reason why Minority Report and artefacts like it work, why they stick in culture; and it’s because of design. David Kirby really analyses the use of design to convince people of certain worlds and world building. John Underkoffler was the guy who designed the gestural interface and then went up to set up a multi billion dollar company based on the excitement generated by Minority Report to build it but obviously it didn’t work we don’t have them…

All that is to say is that basically the reality, believability and tangibility of the designs for John Underkoffler and actually for Minority Report more broadly, is what makes them stick; the reason they were enticing is because they seemed somehow grounded in reality. And there’s lots of detail in that film to bring them out. For instance, there’s a part where when Tom Cruise is swiping across the interface, there’s an error and one of the windows doesn’t come with him, he has to go back and pick it up and those sort of details, bring out the believability of it.

I’m not going to go on about Minority Report anymore. I just wanted to use it to show this connection between imaginaries, design and futures. How the futures we imagine are informed by and inform the stories we tell and how design is a sort of connective tissue that bring both fictional and future imaginaries to life and make them convincing. Because, despite being a complete fiction, as a result of Minority Report we’ve seen probably billions of dollars invested into these speculative technologies at the cost of less glamorous or profitable things like climate intervention or medical science.

[Here there was some chat about pull from the future, promissory rhetorics and projectories not captured]

So now I want to talk about the way that design is used to construct imaginaries, and the way that you can then start to unpick, unsettle and challenge them through critical practice. And this involve the use of metaphors, charisma, and tropes that draw on science fiction. Earlier on I mentioned Haunted Machines which is a project I ran with my friend Natalie Kane, who’s a curator at the V&A. We started this in 2014 and were really interested in the question of why so much of the emerging technology of the time; voice assistants, Internet of Things devices and so on, were wrapped up in occult language and metaphor.

Once you really start to get into the weeds on this, it’s more than just colloquial and coincidental. We did lots of work here and there’s lots of great social science about this. Essentially magic is a causeless technology; you push button get thing, there’s no work that has to be done on labour involved in that process. Secondly it associates the technology with secret, hidden or forbidden power which also goes to making technology really aspirational since power, speed and control are so revered in society. But it also reveals something about how we imagine technology.

We perhaps like to think that technology and innovation are closely aligned to science but scholars have really shown that technology and innovation respond to deeper, more human and existential desires and fears but dress it up as science in order to give it credibility. For instance, Anthony Enns, explored the ongoing hold that psychotechnologies (brain reading technology) has over the imagination and innovation space (see recent neuralink news)…

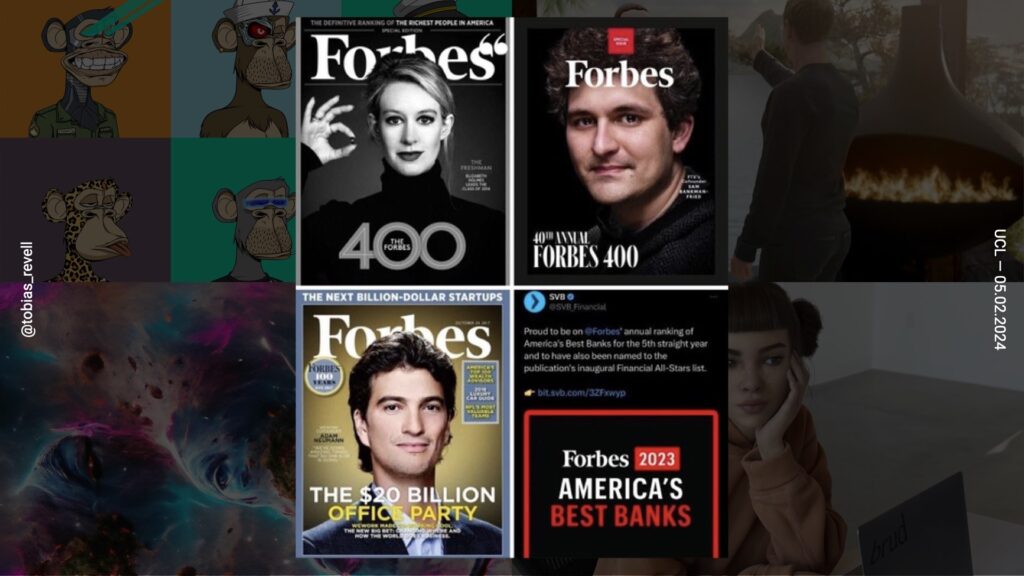

Most technologies aren’t really answers to things; they’re charms to make you more powerful, more beautiful, help you live longer or give you access to secret knowledge. Anyone who’s watched Mad Men would know this but I think we assume that somehow the development technology is a rational science that doesn’t tap into desires or emotions that it’s based on, like, scientific principles. And so, like any field that promises the solution to spiritual, existential crises, it fills quickly with charlatans and criminals.

[A quick game of ‘Name that Criminal’ ensues.]

Charisma is really important here, there’s a reason that we keep revering and looking up to these people. William Stahl, who really analysed this enchanting effect that technology had with the early introduction of the PC talked about the important of charismatic figures, sage-like or even messianic who became idols and prophets as a result of this narrative framework that developed around technology as secret, powerful and tapping into needs and desires.

So as well as metaphors of magic, power, speed and control and great charisma, technology draws on pre-existing tropes and imaginaries we have in order to slip it into mainstream acceptance.

So this is Ai-Da which is claimed by its creator, Aiden Meller, to be the first artist robot in the world. And obviously, like a lot of these projects, very little is given away about how it actually works, who built it, what the actual algorithmic processes behind it, but a lot of work goes into presenting it and framing it. In this case, for a hearing in the UK parliament on the future of the creative industries it is female presenting, it’s presenting as juvenile and it’s presented in these overalls and dungarees to look and feel like a creative or artist as well as, again, somewhat juvenile. This scene is fascinating for many reasons and I have written thousands of words about it. The decision to invite a machine to testify before parliament (which they actually say they can’t admit as real evidence) is ludicrous. Its answers are also pre-recorded, so the whole thing is a performance but you wouldn’t give a tape player the same platform. But the really interesting thing about it is that, very quickly, the politicians and legislators quickly fall into step of treating it like a real human being, they start referring to it as ‘she’ and ‘her,’ and they ask it questions directly. So it’s a really fascinating thing about how the design choices around the presentation of what is essentially an algorithm in a box are eliciting empathy, feeling and sort of status quo relationships from these legislators.

There’s also a fascinating part where Meller talks about some of the engineers who worked on it who said that really it’s the worst form of artist robot you can imagine, right? Because if you want a functioning ‘artist’ robot, that produces paintings like Ai-Da, just use a robot arm. Humans very complicated, messy, lots of limbs that don’t really do much in terms of art-making.

So why insist on this human form? Obviously, the whole thing is to draw on and reinforce an imaginary that we’re super familiar with from science fiction of humanoid robots displaying human-like behaviours. This draws on empathy to make the audience feel an emotional connection (again those deep desires and fears) and also makes it more easily ‘consumable’ as the audience are familiar with this sort of setup from TV and film. There’s also a second imaginary at play which is one that is perhaps more powerful but les obvious and that’s nation-building where scholars have shown now how states and governments are keen to associate themselves with technology to appear future-facing and high tech.

Another great example is the AlphaGo documentary from DeepMind. So in 2016 DeepMind beat the world Go champion, Lee Sedol and they made this documentary about it which obviously gives DeepMind the opportunity to frame the whole narrative around what they’re doing. And because this is film, they also draw on tropes. So on the left, for instance, is a scene where Lee Sedol realises he’s about to lose, and they have this long lens of him outside smoking a cigarette over melancholy violins. And this on the right is a scene from the very end where one of the advisors is playing with his daughter at sunrise in a vineyard and is saying, how excited he is about the AI future. The whole thing is very well done and choreographed to tell a very familiar David-and-Goliath story of DeepMind, a team of dozens of genius computer scientists, owned by Alphabet, one of the world’s largest and most powerful corporations beating a Korean man at Go. Which on the face of it is an outrageous framing, which is why there’s lots of discussion at the beginning of how complex Go is, how it’s ‘uncomputable’ as a way of showing how DeepMind have not only beaten human intuition and gestalt that Go apparently requires but also this insurmountable mathematical problem.

This connection to games is also really interesting, around the same time IBM put out Watson to win at Jeopardy! And there’s a deep history of AI, computers and chess. The mainstream imaginary of AI (and AGI in particular) involves AI being as good as, if not better than a human. We already have computers that can model whole-Earth weather patterns, or simulate huge crowds moving through space, or image distant galaxies, things that no human can do but thanks to collective imaginaries we’ve set benchmarks of ‘good’ AI as one that has the intuitive and gestalt properties of human thinking. Which is why these folks are so focussed on making AI that can make art or win games; it is a way of disenchanting these human activities and skills, showing that they are calculable, controllable and computable. It’s profoundly nihilistic.

The final thing here is the ‘so what?’ ‘So you’ve built a computer that can win at a game, so what?’ And this is where there’s usually a clever rhetorical swipe and the story turns speculative. You’ll often find here as you do in AlphaGo and in the shorter Watson documentary an extended claim that victory at this one very confined benchmark equates to curing cancer, solving climate change or alleviating poverty. Even though scholars have shown that there’s little result from these displays and performances other than increased funding and hype.

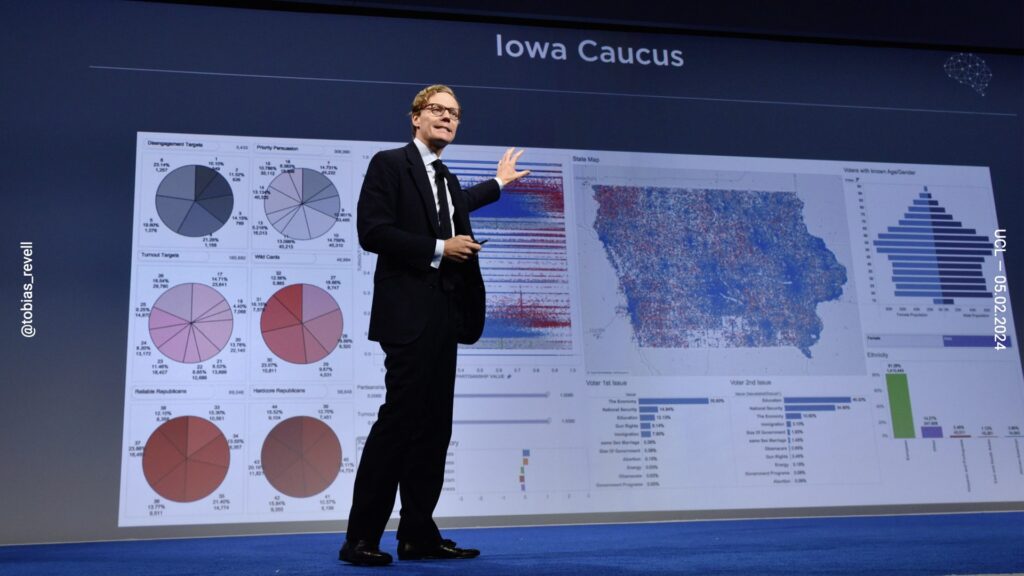

And then you’ve got things like the design of power and complexity. This is another big trope in AI. This is Alexander Nix, who was the head of Cambridge Analytica who were famous for stealing a lot of data from Facebook and claiming to be able to predict and influence the outcome of elections. Studies since have shown they had no such power whatsoever. They did steal thirty million Facebook profiles but they didn’t have anything fancier than a big Excel spreadsheet. The point is, when you see him or read about him, he’s always described as very charismatic. Like our previous charlatans, that presentation, in this case of a slick, public school guy who’s well connected is really important. And the things that Cambridge Analytica really relied on to bamboozle people is scale and complexity. All of their comms is big numbers, complex terms and ideas. And whether it’s in cinema or in real life, this is often used to construct an AI imaginary; this idea that somehow it’s bigger than us, and we can’t possibly comprehend it. It was used by DeepMind to describe Go as uncomputable and beyond the comprehension of a human. This apparent complexity is used as an invitation to ignore how it works and, again, to secure that secretive, magical power.

Then there’s journalism and media. If you Google ‘artificial intelligence,’ you get these humanoid figures that are usually blue with lots of lines going everywhere accompanied by numbers and data. This is no true representation of AI, and lots of groups are exploring alternatives, but it is a pretty dominant aesthetic metaphor used in mainstream press and reporting which goes to secure an imaginary that…

…is also reinforced in cinema. We can see, and are likely all familiar, with how the same aesthetics are recycled, because if you’re going to explain AI to someone, they’ve probably seen Ironman so you can use that to build your story on. It’s easy and convenient to hijack those aesthetics for stock imagery, and sort of loop them back through culture over and over again. But of course, at the same time, as we saw in Minority Report earlier, real-world technology is shaped by this set of fictions and stories.

[Pause for chat]

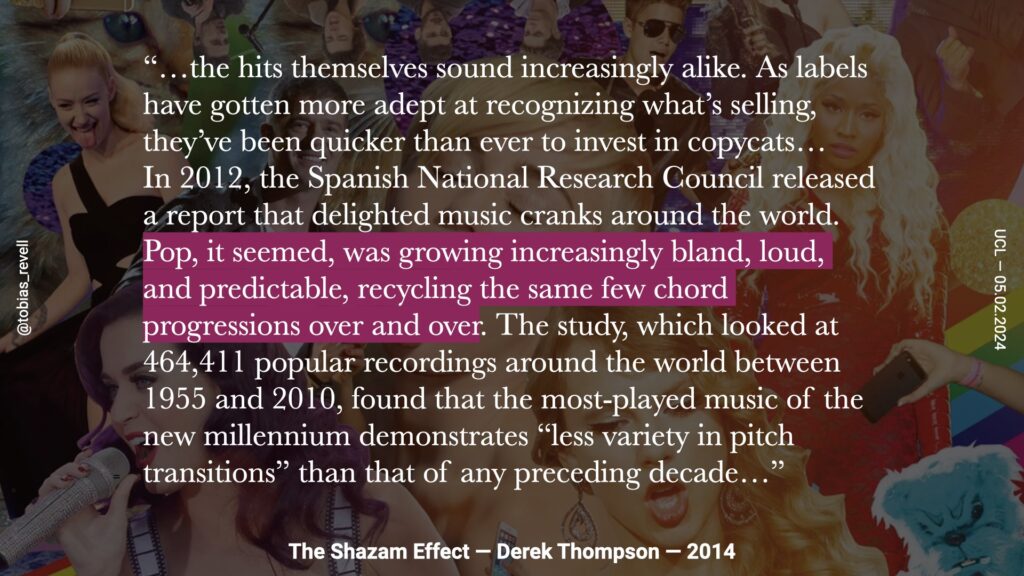

So that was a whistle stop tour of how imaginaries are constructed and how design is used to build them. I want to quickly look at how they’re disseminated and what that means for them. Not only these, these imaginaries created and reinforced, but they also have to get out there in the world. Has anyone come across the Shazam Effect?

So, in 2012, a bunch of Spanish researchers sat down to answer the question; ‘does all pop music sound the same?’ And they found out it did…

So later, Derek Thompson coined the Shazam Effect to explain this; that through things like Shazam, Spotify, and these increasingly available data platforms, record companies had loads of data about what people like which they could then use to produce more music that conforms with what people are listening to. And, as science fiction author Bruce Sterling says; ‘what happens to musicians happens to everyone.’ And so…

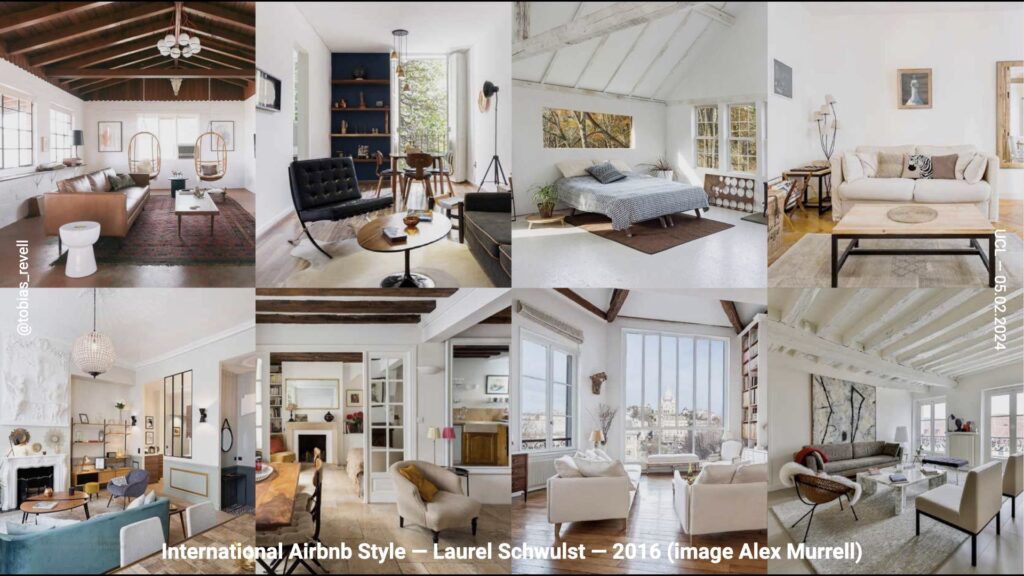

We see this effect in things like International Airbnb Style as coined by Laurel Schwulst. When you’re on Airbnb, you’re trying to attract people to stay at your property and so you look at the other properties that are successful and you design it, present it, photograph it and light it in a way that’s successful for others which results in this homogeneity.

We see the same thing in cars with this Wind Tunnel Effect. There’s so much software and regulation around the design of cars that when you run them through the simulations that are required to make them as efficient as possible, meet the fuel standards and so on that you basically end up with the same slight variations on the same forms.

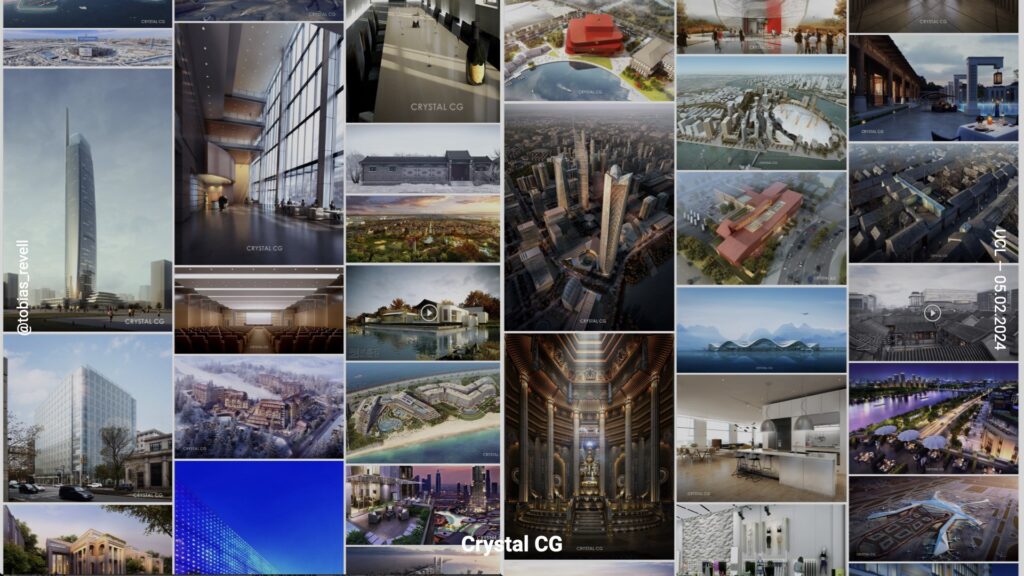

In architecture we also see the same thing thanks to industrial image production. This is Crystal CG who produce renderings for architectural studios all over the world and they’ve produced hundreds, thousands of images. So they know what worked previously. They know what clients like, they know what works in a particular country or city or region. And so you end up with homogenisation of style and design and form as this centralisation of production makes the process less artistic and more industrial.

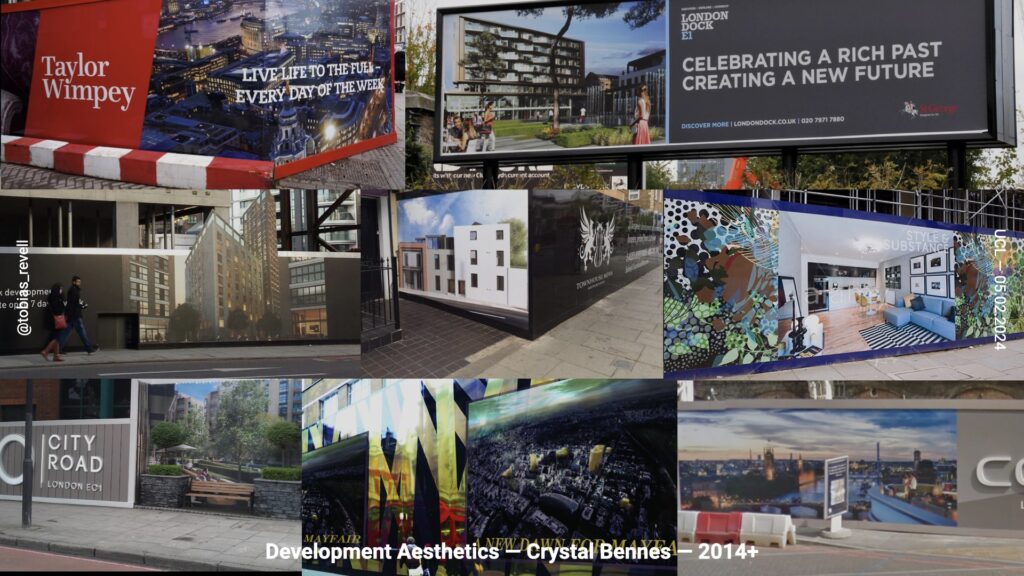

And these renderings are particualrly important because I would contend that these images, printed on these eight foot tall hoardings and plastered all over the city are the most common and everyday way that most people come across the future. They might read the news or watch a film, but every day they’re living, working and travelling around these massive, highly saturated, gorgeous images that obscure the real building site and importantly…

…distract from the actual place where they have a voice in the future of their city, which is in planning notices.

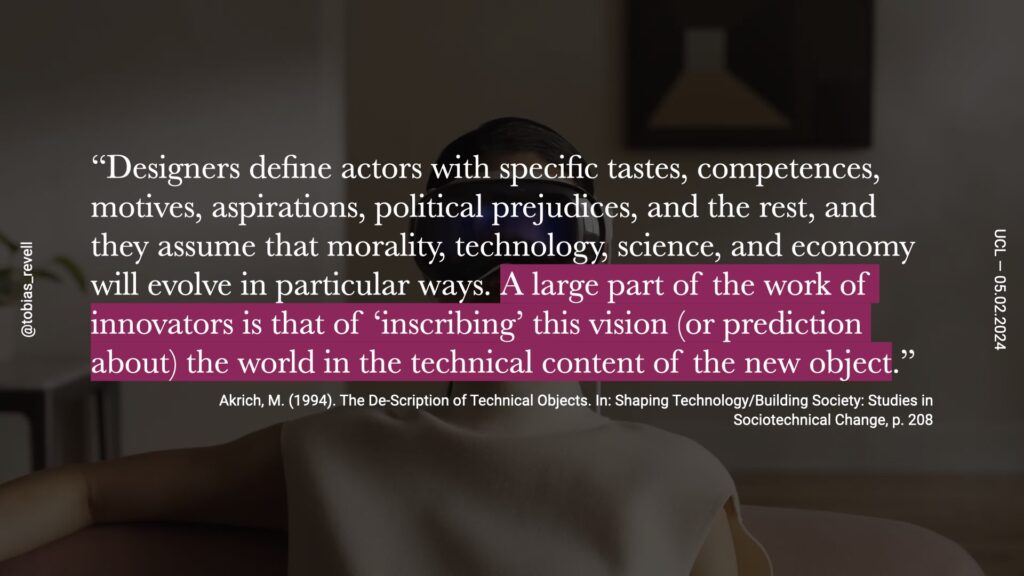

I think the thing to take away from all of this as we move on to talk about what you can do and how you work as critical practitioners is to know that design in this situation is never neutral, that it carries forward pre-existing tropes and assumptions from culture, imaginaries and fiction and embeds them in new objects and technologies. So things like real-world AI are designed, by choice, to conform to expectations from fiction and the imagination, even though it is often wholly inappropriate to dealing with real world problems. Madeleine Akrich writes…

So I want to get on to critical practice, because that’s why we’re all here.

So an assumption that I’ve seen a lot in AI and again, I’ve written about quite a bit is the idea that AI will somehow democratise imagination and creativity. And I love this interview with the creator of stable diffusion, David Holz who says…

This idea, that again, is profoundly nihilistic, that creativity, criticality and imagination are just about making the right tool is provably false and very similar to claims that social networks would liberate, democratise and educate. At the same time as claims are made of ‘democratising’ creativity, these tools and platforms are foreclosing imagination to try and make it conform with what AI developers want.

The title of this talk, and it’s related to my thesis title as well is ‘Design and The Construction of Imaginaries’ which is an allusion to an amazing paper by Carl Di Salvo – ‘Design and the Construction of Publics.’ I always point to this work for your one-stop shop on how critical design works. He suggests that design has a role in building public discourse, not just solving problems, he says…

Di Salvo says that publics assemble around issues. This issue might be a new building, it might be a broken toilet, it might be you know, being a parent, it might be unaffordable rent. And very often those issues are designed such as with a building, app or service. So Di Salvo extends this and says that the way that critical design works is by inventing the things for an issue to assemble around. And when you’re talking about things like AI and the sorts of things that are quite ephemeral and tricky to pin down, there’s a powerful role for critical practice to materialise the issue so that people can then assemble around it and talk about it.

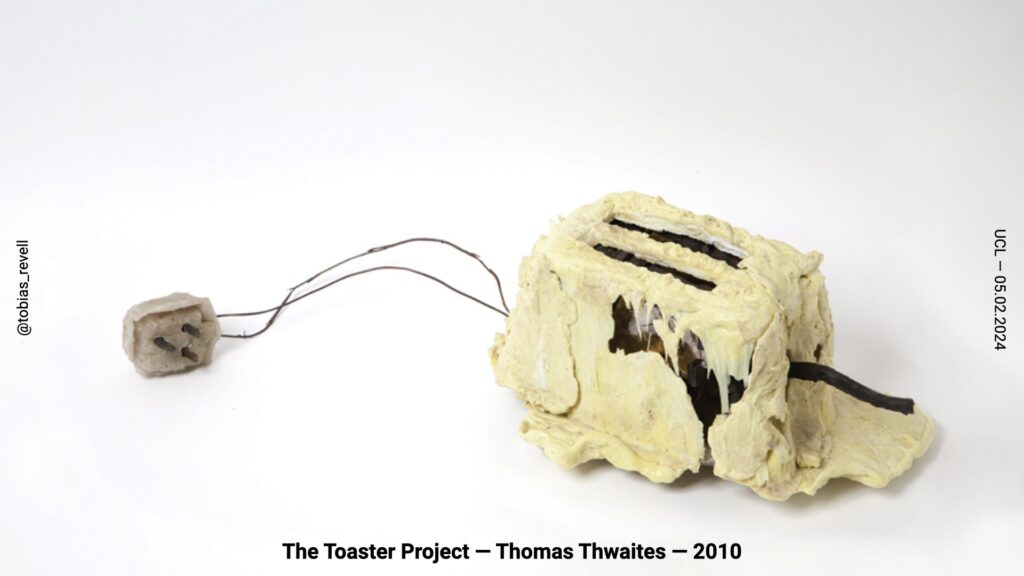

So a one of the most well known projects that does this, and one that Di Salvo writes about is Tom Thwaites’ Toaster Project. So Tom Thwaites set out to answer a simple question, which is; ‘can I make a toaster?’ He had to make everything himself, had to smelt all the metal and form all the plastic and reated this great series of YouTube videos, I think became a little documentary and a book. So why? I mean, we already have toasters and as Di Salvo says, he’s not solving anything. The main thing is how the projects reveals how much we take for granted these incredibly complicated supply chain processes that go into a really simple object. Di Salvo calls this a ‘tracer;’ it traces the outlines of a thing that’s otherwise invisible, which is the whole supply chain, industrial set of processes and technologies that produce this really simple object. It reveals them to the audience by saying this is a ludicrously complicated, globalised, exploitive, and wasteful product. So by revealing this thing that’s otherwise invisible or obscured he brings an issue to the front which is otherwise quite difficult for people to understand; supply chains, materials, all that kind of stuff. So this is what what we mean by using design to unsettle or untangle certain tropes.

So Di Salvo calls this a ‘tracer’ but the other type of project in critical practice of design is what he calls ‘projectors.’ You’ve probably heard of speculative design and Tony Dunne writes in his thesis…

Di Salvo says that these projects work by showing how things might be otherwise to reveal the way they are which might be otherwise hard to see, because it can be hard for us to challenge our assumptions about life; think again of the Start Trek ‘no smoking’ sign.

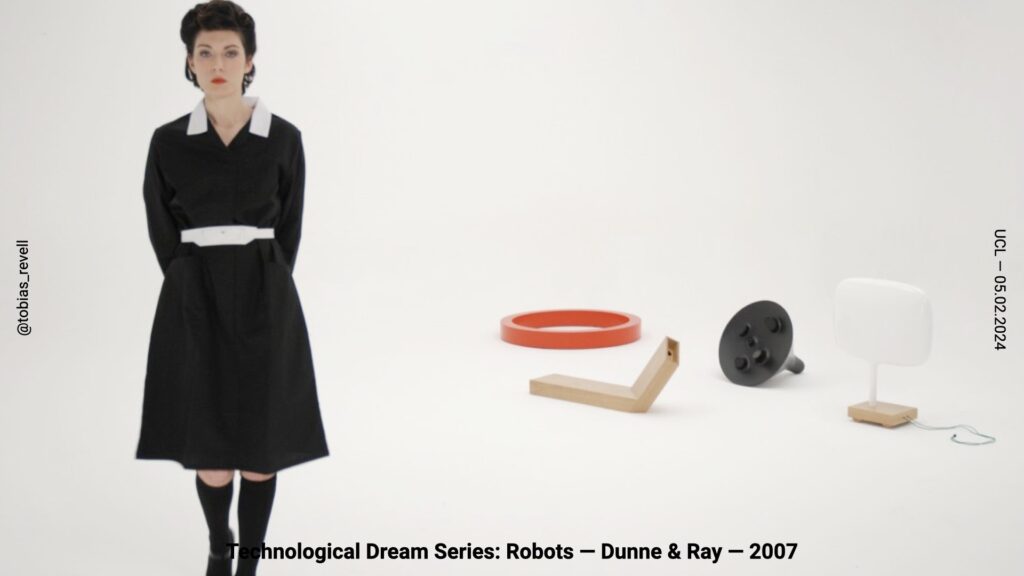

So this project for example is called Robots but would you think of any of these objects as robots? They all have characteristics of robots. The one with the one with the looks a bit like a lamp has to be plugged into the wall in order to work so it can’t move around as much as it would like, the L shaped one is my favourite but has to be held at a particular angle in order to work which requires it to basically rest in the crook of your arm or it won’t work. All of these things are designed to have the behaviours of what we might assume a robots; they have movement, they have autonomy, some sort of agency, arguably, but they look nothing like ‘robots.’ They don’t look like metal humanoid figures, or little dogs or machines but by projecting forward (or sideways, let’s say because it’s not suggesting a particular time) and saying ‘this is how things could be otherwise’ it reveals the assumptions that we have taken for granted; all those tropes that we talked about earlier that are constructed around AI and technology.

So that’s tracers and projectors, used to reveal hidden assumptions. But I also think the hack or exploit is really an important tool. I’ve spent far too long going down to speedrunning rabbit hole which is completely fascinating. So speedrunning is simply people competing to complete a game as fast as possible by any means possible. And the great thing about that challenge is that speed unners don’t see the video game as the designers intended it. They don’t see it as a world with the narrative and certain mechanics in it have been designed, they almost get to the layer underneath the actual construction of it; the architecture of the actual game engine itself, and try and find hacks and exploits in the underlying mathematics really to find a way through. And these hacks require really explicit and sophisticated knowledge of game engines and architecture in order to spot the exploits.

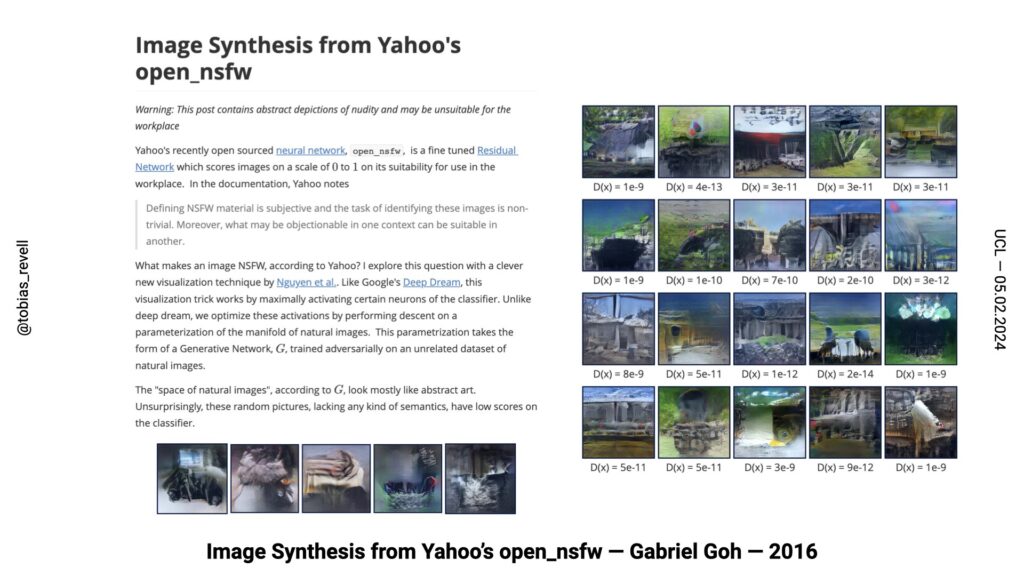

And I like seeing the same concepts on approaching technical systems in critical practice; that ability to see beyond the thing as it’s presented and unpick the reality underneath. For instance, Gabriel Goh took Yahoo’s Images’, not safe for work filter, and turned it all the way to zero to ask; ‘what’s the least pornographic image possible? What if we undid that algorithm, laid it out and turned everything to zero and then rendered what it would give us?’ You end up with quite pastoral and bucolic scenes. You sort of get the sense of classical architecture, green, beaches, sky, that kind of stuff. And this is a similar sort of tracing project that uses exploits to reveal a system. It’s taking the thing that we’re that we’re given, and saying, ‘I’m just gonna lay out all the pieces of it and try and figure out where they come from and the decisions that were made.’ Because someone programmed this, it’s not accidental, someone decided what the least pornographic image possible should be and trained this system on it.

An important note here is how, like a lot of good critical practitioners they document how they do this right because that’s really where the knowledge is. It’s not in the thing itself. It’s in the journey to get there and that’s, that’s really important. They’re all documenting what they did and what they revealed.

I’m going to talk about one of my own works really quickly, which was an Augury a project I did in 2018 with Wesley Goatley, who’s a sound and data artist by training and we’ve worked together on lots of projects. So augury was an ancient divination technique used by the Greeks and Romans which involvd looking at the flight patterns of birds. So they basically say; ‘all the birds are flying West, therefore, we must go to war’ or ‘the birds are flying East therefore, we must go to war.’ It usually ended in ‘we’re going to war.’ Fundamentally, it was a belief that the birds were messengers from the gods.

So we created a sequence-to-sequence machine learning system that trains on ADS-B data of the flight pattern of planes over 50 kilometre radius of London for about four or five weeks and put it next to the latest tweets about the ‘future’ from London at the same time, and then train this machine learning system so that once it was in the gallery, if you asked it for a prediction, it would just give you complete garbage, because there’s absolutely no association or causal connection between these data sets. But what we wanted to do is untangle a lot of the way big tech was talking about AI as almost prophetic in its power while obfuscating the way it actually worked. And so the point of this satire was to say, ‘given how little we know about how often these corporate machine learning systems work, they may as well be the flight patterns of birds and planes.’

And, as I said before, documenting, reflecting, talking with a great collaborator about what you’re doing, the choices you’re making and the thing you want to unpick is super important. Especially as this was one of our first time working with machine learning. And as we’re doing it, it’s revealing to us something about the way that computer scientists or engineer think about things like corpuses, data sets, epochs and so on. What are the corners cut? The conveniences made? The assumptions inscribed in these tools.

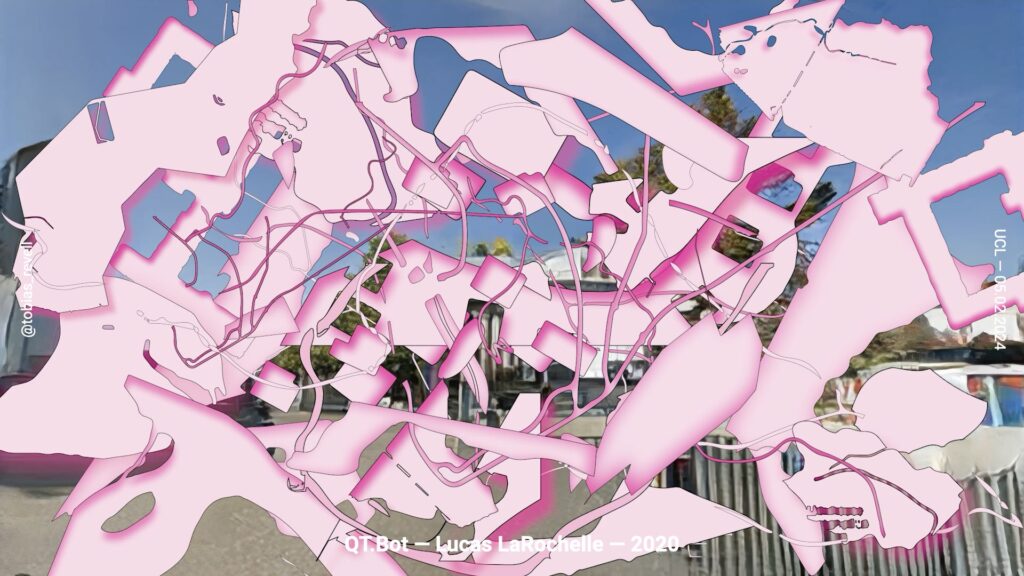

So if that’s a ‘tracer’ what can ‘projectors’, alternatives, look like? This is QT.Bot by Lucas LaRochelle. LaRochelle, did a project for years called Queering the Map where they gathered stories of queer experiences all over the world, and then pin them to Google Earth. So basically, people would would say, give an anecdote about how they met their partner, or maybe had a negative experience as well as a queer person at a certain place on Google Earth. This map is now huge, it must be tens of thousands of different people’s testimony. But then LaRochelle trained a machine learning system on that data, on the stories and on the images of the places to generate an arguably queer AI with data is fed it that is very different from a normative, heteronormative data set.

And another speculative trajectory for AI that lots of people are making is how it might enhance our relationship with the non-human world. Such as with the Ecological Intelligence Agency from Superflux. Sascha Pohflepp captured this idea for me, that what AI gives us and should be giving us, isn’t the ability to replicate things that humans can already do but to extend and enhance our ability to understand things that are too fast, too slow, to huge or too small to be comprehended by us. I guess that’s where a lot of the science is pointed but what if that was the imaginary we held too? Not one of speed, power and control but of understanding and empathy and care enabled by the ability to crunch vast data to the human scale.

So what can I leave you with as critical practitioners? I hope I’ve talked about how imaginaries are made and disseminated and how design is used to reinforce those but also how critical practice can use methods like tracing, projecting and exploits to reveal and unpick them, to assemble new publics around the ephemeral and loaded imaginary of AI and other things.

I called this little section ‘making traps’ because I think really, taht’s what all this is about. Whether you want to convince someone of a science fiction future, or invite someone to challenge their assumptions you’re making a trap. Benedict Singleton, reflecting on Villem Flusser writes that…

Fundamentally, no one is creating anything new. The trap maker simply reengineers existing tendencies for a new outcome. Think about a simple rabbit trap; you bend the branch to hold the elasticity, you know the rabbit wants to eat a certain type of bait and follows a certain path and thwack! Rabbit stew. There’s no fundamentally new thing here. All of these futures are traps; drawing on a mastery and sophisticated understanding of things that already exist – aspirations of power, control and speed, stories and fictions of robots and all powerful machine – and pointing them in a new direction that’s favourable to whatever imaginary you want other people to buy into. The question is whether you build traps that keep us in the status quo or ones that break us out of it.

Thanks.

Recents

I contributed to the Service Design College’s Futures and Foresight course on some of this stuff but in a more applied way. You can no go and look at it if you want but I think it is behind a paywall.

Short Stuff

Very short. Trying to spend less time reading newsletters and more time writing PhD even though this transcription took probably four hours.

- Future of Money 2024 Awards are open; ‘The National Wealth Service’

- I haven’t come across anything gushingly positive on the Apple Vision Quest (but then I don’t tend to read uncritically gushing positive journalism). Here’s some from Paris Marx about why it doesn’t make sense,

- Max Read suggests that Kyle Chayka gives too much weight to algorithms and feeds in his analysis of why everything is the same.

- An apparently infinitely generative AI channel which has stopped (as of when I looked.)

- Check out this wild story of a Hong Kong worker tricked on a video call into handing over $200m by deepfakes of a company CFO.

- (I am borrowing from Webcurios – I don’t know how he has enough time to put that thing together) Animated mechanical watch!

- An 8k map of 1444 Europe.

- Check out Lex and Anna chatting about machines and creativity!

I’ve been reaching out to catch up with people now I’m emerging from my convalescence including folks I haven’s spoken to since before the Cov. If you wanna hang out, let me know and let’s hang out a bit. Ok, love you bye.