The weather’s moody and unpredictable, which makes it difficult to talk about. Like a troubled relative that you brush off when asked about in polite company. You don’t want to privately acknowledge that what you’re witnessing is a very terminal collapse and so you mark it down as eccentricity and hope that it’ll just go away.

Years ago I did a project (naively and clumsily in retrospect) mapping the flow of power through a very Eurocentric view on history. I still hover around the thesis that the power remains the same but the institutions mutate and I’ve been listening to and reading a lot of stuff about ‘deep state’ conspiracies recently, particularly the aesthetics.

Anyway I thought it might be fun to mess with it in the context of this ‘deep-deep state’ conspiracy I sort of speculated on. Let’s get the hashtag #DeepHapsburg going and maybe write a Twitter bot that just replaces all the Q nonsense with things from the Austro-Hungarian empire. What do you think? Good idea? Pointless distraction? ‘Schleswig-Holstein; Tell The Truth #ReleaseTheProclomations’ #WherePalmerstonGoesWeGoOne‘

Practical Thinking

At the moment, the planet might seem poised more for a series of unprecedented catastrophes than for the kind of broad moral and political transformation that would open the way to such a world. But if we are going to have any chance of heading off those catastrophes, we’re going to have to change our accustomed ways of thinking. And as the events of 2011 reveal, the age of revolutions is by no means over. The human imagination stubbornly refuses to die.

David Graeber – A Practical Utopian’s Guide to The Coming Collapse

I’m sure you’re aware David Graeber died last week. I didn’t know him at all but he was a significant influence on my political thinking through my student years and beyond. I came across Debt while working in a bookshop, read that, then went back and read everything else. I remain pleasantly surprised, word-eatingly so, that the post-apocalyptic wasteland ‘marketplace of ideas’ Twitter dot come hasn’t torn his legacy apart yet. Instead, the expressions of loss and meaning in his work appear genuine. His words, activism and general optimism seem to be universally admired and acknowledged.

Thinking about it, there are two things about Graeber’s writing that makes him stand out and may account for this wild exception of why the piranhas of the Irish microblog haven’t turned on him yet.

Firstly, he never seems to trash anything. Nothing was unsalvageable; everything could be a tool put to other uses, subverted and improved. Similar to the way Pratchett never had true villains, just individuals with different, maybe misguided motivations, Graeber’s optimism is rooted in a real belief in change and an optimism for the world to come. This appeals very much to (and possibly formed) my designerly strategy mindset. In writing about Occupy, he describes the strategy as about being cleverer and understanding ‘the system’ better than the the system itself; from occupation to taxation laws. Institutions, systems, organisations and machines are all assemblages that are exploited in a particular way by those who hold the levers of power. Instead of resorting to fire and brimstone, identify those levers, figure out where they’re weakest and exploit them yourself.

The thesis of Debt is a demonstrable argument of this kind: Graeber suggests that ‘Abolish capitalism’ is unfeasible, unimaginable and even undesirable to most and may be snarled up in left activism forever. However, ‘Abolish debt’ hits a chord with a wider audience, drawing on the near-universal experience of debt while identifying it as the actual technical thing that underpins the inequities of capitalism.

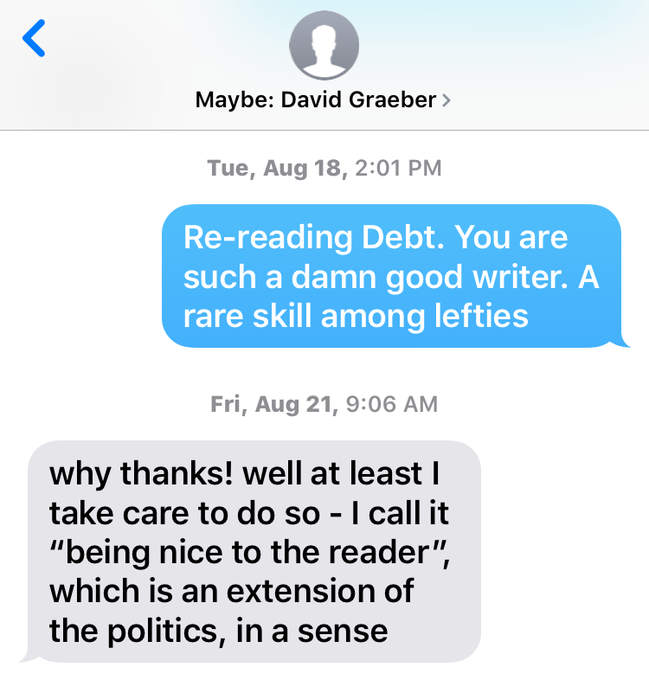

This ties into the second point; knowing how to communicate difficult, complex ideas to a wider audience. After all, it was Graeber who (reluctantly) took credit for the ‘We are the 99%’ slogan.

What this means for his writing is that it’s actually readable. I half-joke a lot that I hate reading but that’s because it’s half true. Reading is hard and very often incredibly boring. It is a physical effort involving squinting and an intellectual effort involving memory and thought. Just like a designer, you, as a writer, have a job to make that effort as easy as possible for your reader so they can get to the actual substance of what you’re describing.

I’m hardly unique in suggesting that the intellectual class reward obfuscation and dodging and glamourise it as ‘nuance.’ Fuck nuance. You don’t nuance a toaster or a fridge, which is why everyone knows how to make a cheese toastie. Graeber’s writing was popular because he made difficult ideas easy to understand through applied examples that drew on most folks’ experience and in doing so progressed not only society but his field of thought. Maybe it’s because I’m an educator but I don’t believe you can move ideas forward if you’re not willing to be generous about inviting other people along with you. So much bad intellectuality is about protecting, hoarding and demarcating those ‘in the know’ against everyone else. More crucially, and particularly for left, liberal stuff, writing and theory is riddled with an unspoken notion that if you, the reader, don’t understand the ideas, then it’s your fault for not being educated, aware or revolutionary enough. Reading Graeber felt like being warmly and generously introduced to the interesting kids at school you thought were way out of your league.

A Practical Utopian’s Guide to the Coming Collapse explains his whole philosophy in one title – pragmatic, optimistic, straight-forward but grounded in serious cynicism and fashioned through humour. I hope there are more Graebers in the years to come or we’re going to have big problems.

Short Stuff

There’s a lot of short stuff this week. So much that I’m saving some for next week which is a Content Strategy.

- I have a growing theory that Death in Paradise and Lost belong to the same universe. Ask me about it some other time.

- The Navier-Stokes equation and the unresolved problem at the core of it is one of my favourite mysteries of maths. You may have heard me bang on about it to you some time: The equation is very good at predicting how fluids move at any scale up to the galactic except that as you get closer and closer to an infinitely small scale they approach infinite speed, which is impossible. I watched this terrible film recently in which the problem was given much less than a starring role next to Chris Evans’ fatherly redemption story, despite being mentioned all the time. Don’t watch that terrible film. Watch this Numberphile about it instead.

- Speaking of protocols and file formats last week. Check out this amazing event from the New School next Monday.

- I linked it up the top there but, a very exciting thing to happen for Blender Eevee is someone has made an add-on that simulates the effect of global illumination. Eevee is Blender‘s newish real-time rendering engine made to compete with Unreal. The cost of real-time rendering is you’re never going to get the top of the reward curve of “realism” that comes with really superheating your graphics card for hours like used to happen with Cycles – the other Blender rendering engine which uses the much slower but more accurate ray-tracing lighting method. Real-time (or rasterised) rendering always looks like a video game – harsh lighting, high contrast – unless you engage in loads of trickery. Physical reality is generally softly lit and coloured from all directions – called global illumination. This hysterical gentleman does a good job of explaining it, but I’ll be messing around with that this week, for sure.

- How does Matt Webb do this every. damn. day?

- Your favourite solarpunk and mine Jay Springett has a new channel – ‘Come Internet With Me‘ which sort of explains itself.

That’s it. I love you as always. Sorry for getting frustrated at academic and intellectual culture. I know Certain People will lambast me later and tell me how I’m wrong but I don’t think they’ll ever change my mind: There’s a reason that good ideas keep losing out to conservatism and wilful ignorance and it’s partly our fault for making them hard to get at.