At least it’s light when I wake up now. I miss the dark though; the quiet solitude of those first few hours, when it felt like everything else was very far away. My neighbour wakes up at 9 every day and opens their curtains and now it feels like they’re oversleeping since it’s been light for a few hours already.

I’ve edited down and put my tags back over there ←. Hopefully this makes it a little easier for at least me to search this thing and find my old posts which is part of the point. I started fidgeting with setting up the newsletter version of this too. There’s about thirty folks subscribed but it’s still a bit arduous so for now I’ll park it and pick it back up when I get a minute.

The Sailing Ship Effect

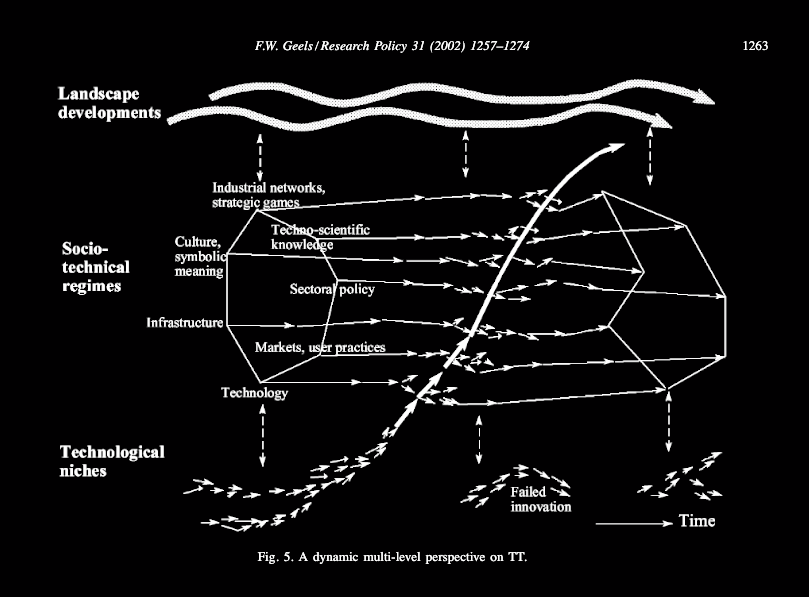

I was sent Frank Geels’ Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes by Justin the other day as a neat segue into all the stuff I’ve been reading and writing about expectations and innovation recently. I immediately recognised a bunch of the diagrams – probably from Benque’s spam posting.

Geels describes the way that technologies emerge from niches, travel through the dominant ‘technological regime’ made of markets, user preferences, legal and insurance policies and cultural meanings before becoming embedded in the landscape. In particular, his paper here focuses on the development of steam ships in the late 19th and early 20th century and how they went from niche applications in canals to mainstream use enabled by and enabling shifts in the physical and technological landscape to support them.

However, his account doesn’t acknowledge the role that imaginaries and expectation play in technological development. My work is about the imaginaries around so-called AI and the social imaginaries, expectations, hopes and fears of AI seen throughout popular culture and the media pre-date any actual technical applications of AI by decades. The imaginary of AI predates actual AI – arguably still. Now off the top of my head, I can’t recall a great popular culture imaginary of steam ships that predates their invention. There aren’t futuristic paintings from the 17th century showing alien looking steamers that I can think of. In fact, as Geels describes it, the steam ship was an incidental innovation that emerged as a product of social conditions (greater emigration, the desire for more regularity in shipping etc.) and trial and error. So when did the imaginative dimension of technological innovation start to emerge? When did technological innovation begin to be driven by in whole or in part, imaginative longing?

This may not be the answer but at one point he compares the way that wooden sailing ship building was seen as a craft with all the mysterious and esoteric tacit knowledges of an art form while steam ships were part of a scientific lineage:

While shipbuilding had always been a craft-profession, it gradually turned into an applied science, something upon which most shipbuilders initially looked with unveiled hostility.

Geels, F. (2002). Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study

For instance, steam ships underwent prototyping, testing and other processes we might now take for granted in technological innovation but at the time were new methods. Wooden sail shipbuilding was assumed knowledge, passed down from masters to students with little reflection, questioning or innovation except over long time periods. Now, most technological innovations emerge from science and I tried to read Bernard Stiegler once to understand this but couldn’t so just take it as assumed knowledge.

So, I wonder to what degree scientific process and methods are better at inculcating imaginative new potentials? Loads of people have written about how the conditions of the laboratory and research setting prefigure certain priorities and futures and for instance in Karin Knorr Cetina’s work, how the specific ways of interpreting natural phenomena shape epistemology. Could we argue that craft, (broadly speaking) with a focus on demonstrable excellence in one particular type of task turns the imagination away from other possibilities that might emerge from technical processes? While scientific methods, with their emphasis on observation and experimentation are more fertile for new imaginaries?

Geels’ paper is known for incidentally describing the Sailing Ship Effect where advances in a new technology (steam ships in this case) force the existing dominant technological regime to innovate at an accelerated pace. Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, designers and shipbuilders suddenly found they were able to automate large parts of their vessels to reduce labour costs once the threat of more reliable and faster steamships became real.

Anyway, it’d be great to speculate that is what Instagram are doing by crowbarring in yet another ‘feature’ in the form of ‘Rooms’ but they’re not, they’re just flailing to keep up with Clubhouse. Instagram, if you’re reading, send some of your people to a design school.

Short Stuff

- The Disco Elysium Final Cut is getting its release date this week for this month. I will be playing it again, I will be telling everyone all about it again.

- Hopefully you’ve seen Claire Evans’ thoughtful and insightful writing on xenobots, but it’s here if you haven’t. This is one of those things that’s like the opposite of NFTs – genuinely interesting, exciting and challenging to our understanding with enormous possibility. Rather than just about acquiring capital.

- There’s so much stupid stuff right now. It just feels stupid. Just like profoundly stupid when we were doing so well. One step forward, two steps back. What emerges from this global horror-cocoon in a few months to a year is going to be total shit because of all the stupid.

- I’m still not doing enough PhD work, leave me alone.

Ok, that’s about the size of it this week. I need to edit a video, clean a bike before it rains and chunk through some emails I’ve been putting off. Love you, write again next week. Let me know if you wanna hang out.