This week I pulled together the slides from the talk I gave at Simon Fraser University last week. I’ve been developing this talk over a a year or two and it goes hand-in-hand with my PhD work so you can read this as a little bit of a scan of that. Thanks to Sam Barnett for the invite. I took the transcript from the recording, regex’d out the timestamps and names and then used CoPilot to tidy it up in chunks, so it’s not quite my voice. For instance, it generated sentences like ‘numerous factors’ where I would have definitely said ‘bunch of factors.’

The recording is here as well if you would rather listen to the original ‘sort of, you know, bunch of ideas.’

Thank you for inviting me to come and talk about Design and the Construction of Imaginaries which is where work and practice has been located over the last 10 or 15 years.

I have several hats that I come to design with. My day job is, Design Futures lead at Arup Foresight, which I’m not really going to talk about that much at all. Arup is a global engineering firm of about 18,000 people all over the world and I sit inside a team that focuses on helping our business and our clients think about the future. And I definitely bring a lot of what I’m going to talk about today to that. But, as as was intimated in the introduction, I’m mostly going to be focusing on the theoretical and practical approach I bring to design which I’m mostly exploring through my PhD as well in my former role as an educator. I’m also going to talk a little bit about Haunted Machines, which is a project I’ve been running with my friend and colleague, Natalie Kane. We’ve been running that for about a decade looking at stories of myth and magic and haunting and technology.

Today, I want to address the question of imagination. Imagination is a socially constructed concept that reflects our fears and aspirations. We channel these through stories, popular culture, media, and most importantly, through the design choices we make in our lives.

There’s a complex web of ideas here that I’ll try to unravel. I’ll also touch on AI, as my PhD work revolves around it but is not really about it. AI serves as a useful placeholder for discussing technology’s role in our imagination. AI has been a powerful imaginary concept for around 75 years, arguably 100 if we trace it back to Karel Čapek’s 1920s play, R.U.R., which introduced the concept of the robot. AI is deeply embedded in our culture, and almost everyone has some notion of it, especially in recent years.

AI is a great example of how technology has influenced the modernist imagination. This influence is relatively recent, primarily emerging in the modern period. I’ll walk us through various aspects of this topic.

Future Foreclosure

Let’s start with the idea of foreclosure. I’m asserting the claim that the future is a foreclosed space. Various competing actors in society try to claim the future and present their vision of what it will be, whether that’s political, technological, scientific, or otherwise. As a result, the future is somewhat foreclosed, and we’re not very good at imagining it. This is an example I love to use with clients when discussing futures and foresight work.

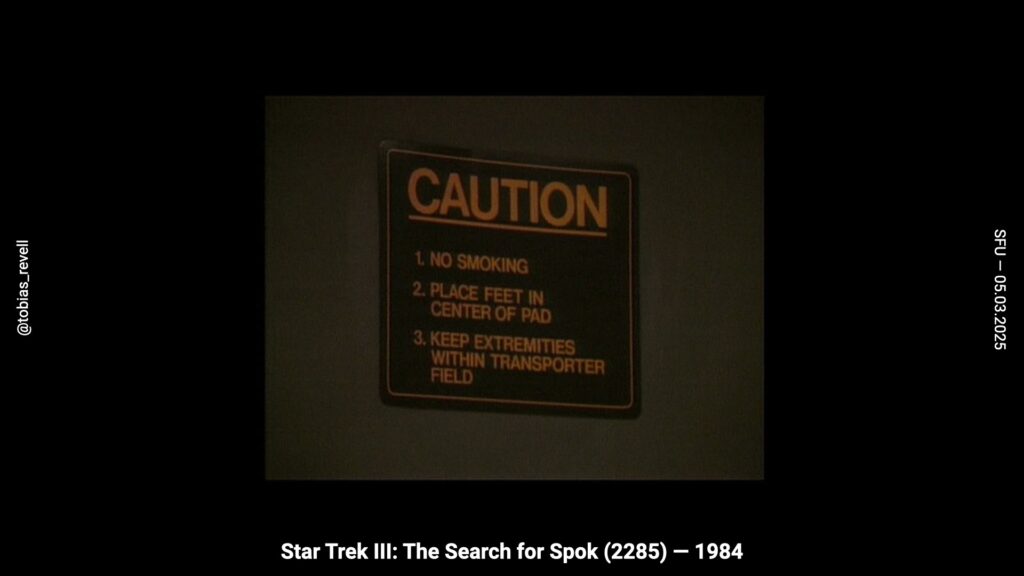

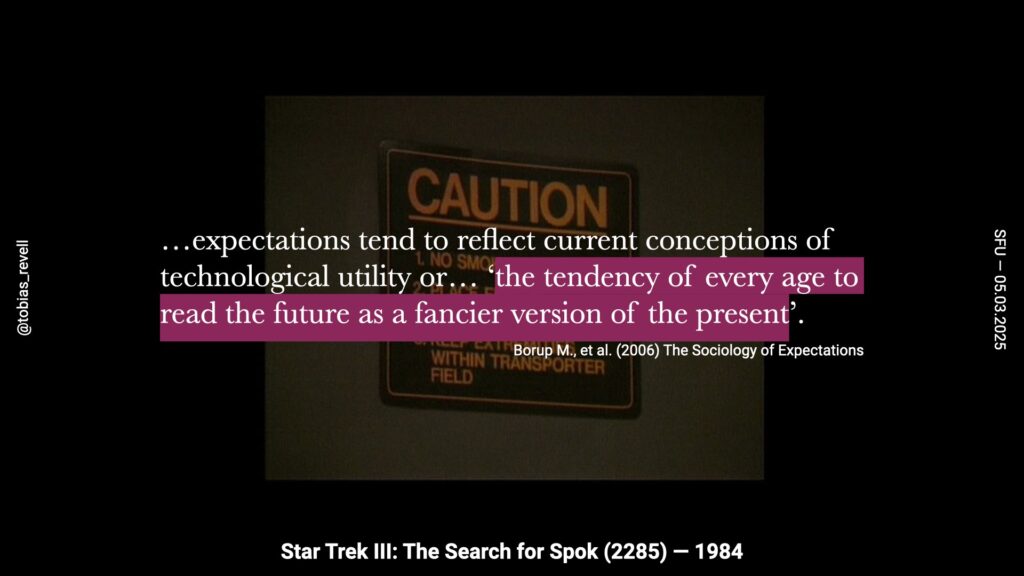

This appears for less than a second during the third Star Trek film, The Search for Spock from 1984. It appears on the wall of the transporter room. This is a point where science fiction is gaining traction and becoming more mainstream, thanks to films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars the decade before. Gene Roddenberry and his team put more budget into the design of the starship Enterprise. Next to the teleporter room, they put up this sign.

What I love about it is that they’re designing a world 200 years in the future, in 2285, where they can dematerialize someone and transport them to another ship or planet, breaking them into their fundamental particles and reassembling them on the other side. Yet, everybody still smokes. The only change they can imagine is this vastly complex technology, but the idea that smoking might not be normal anymore is unimaginable to the designers of this set.

This reflects something Mads Borup discusses in the brilliant sociology of expectations: our expectations tend to be just a fancier version of the present. Most people think about the future in what Andrew Sweeney calls the extended present fallacy; that the future is just like today but with fancier gadgets.

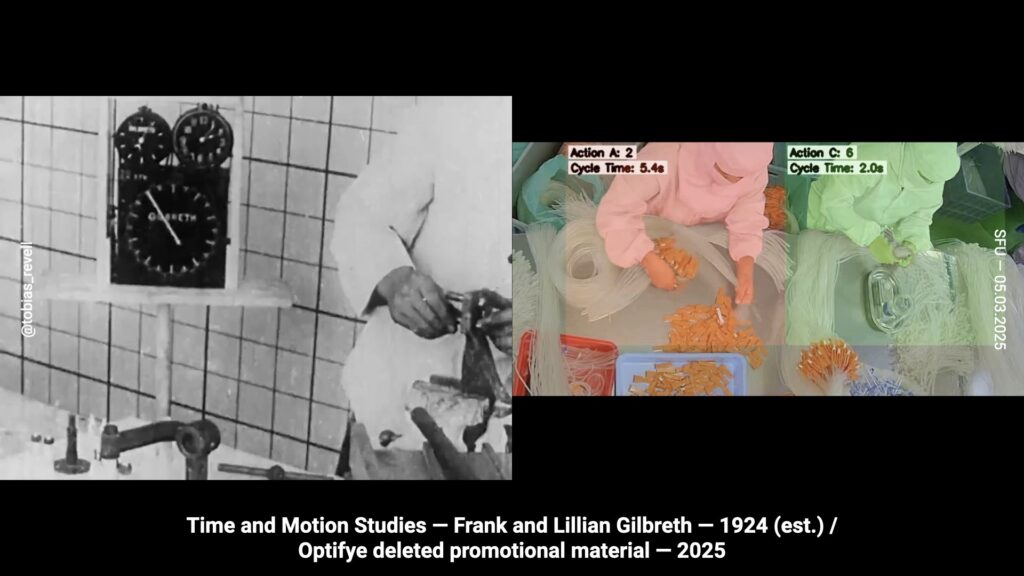

A story came out last week about a leaked promotional video from a Y Combinator startup called Optify. They developed machine learning to track and measure the efficiency of people working on production lines. This aspiration is over a hundred years old. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth were doing time and motion studies of people after the First World War, trying to optimize the movement of workers in manufacturing centers.

The actual concept of what the future is, what work is, what society is, what labor relations are, and what power is hasn’t changed. However, the technology and gizmos have been upgraded and updated. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, by the way, are fascinating people. The film Cheaper by the Dozen is about them because they had 12 kids. This story later became a comedy film with Leslie Nielsen. Despite their large family, they were also conducting serious military efficiency studies.Also Tom McCarthy wrote an amazing novel about them, as really into transcendental spirituality.

David Runciman, summing up 2022—the year of NFTs for those who remember—had a great sentiment. It was also the beginning of generative AI, which was starting to get people’s attention. As a Cambridge economist who runs a fantastic series of podcasts, he said,

This sentiment expresses the massive acceleration of technology we’re witnessing.

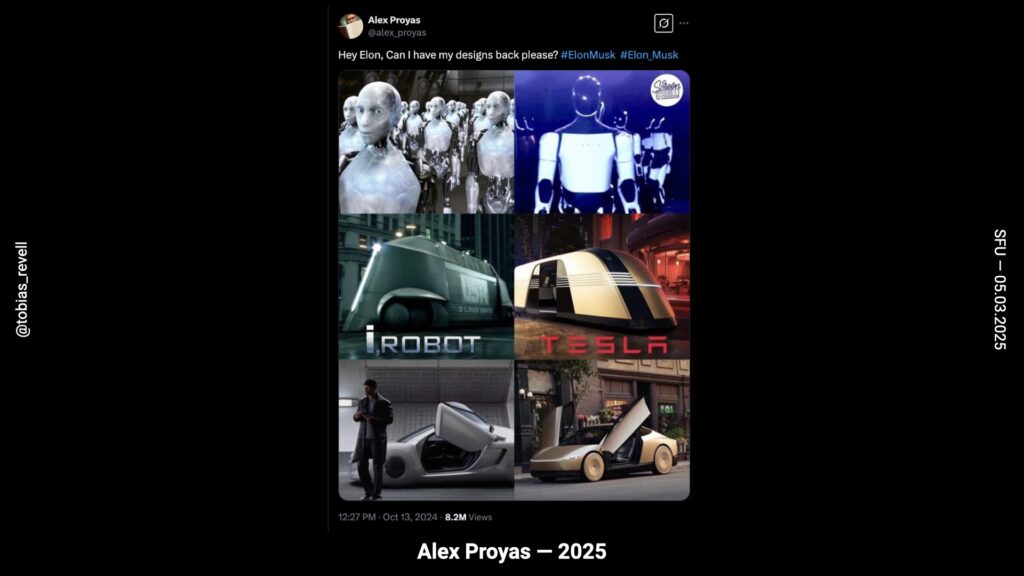

And then, of course, there are the preconceptions that shape these futures. It’s not just about acceleration; it’s also about recreating past fantasies. For example, Alex Proyas, the director and producer of I Robot, highlighted how similar the aesthetics of Tesla’s various products are to the designs he produced in I Robot in 2004. People have taken this image and shown how many of these designs are aesthetically similar to concept designs from the 1920s and 1930s.

This indicates that the concept of a broad, open horizon of the future is not unproblematic. Many scholars have critiqued this idea, suggesting that there are preset expectations and pathways we are constantly being directed down. Designers might be complicit in recapitulating these pathways by drawing on historic designs.

The worst and most nefarious myth of all is the myth of inevitability, which you hear so much nowadays around technology. This rhetoric wasn’t even around 10 years ago. The shift has been from “this might do this” or “this could do this” to “this will do this soon.”

Sun-Ha Hong, in the brilliant Predictions Without Futures, points out that…

Many scholars, including Sun-Ha Hong and Dan McQuillan, have highlighted how the idea of an inevitable utopian future at the end of this progress is used to excuse present failures. Dan McQuillan puts it succinctly: the benefits are speculative, and the harms are demonstrated.

The idea that technology is somehow inevitable is simply not true. Technology is never autonomous, as Langdon Winner would say. It doesn’t pre-exist, waiting to be brought into being.

The example I always bring up is cloning. In 1992, the first mammal, Dolly the Sheep, was cloned by Ian Wilmut. The world reacted by recognizing the potential dangers of this technology and decided to implement bioethics, regulations, and international treaties. This shows that nothing is inevitable; technologies can be changed, stopped, and engaged with through policymaking, regulation, design, and other means.

David Green reviewed about 250 different ethics frameworks on AI and pointed out that not a single one of them explained why AI shouldn’t be created. They all focused on mitigating harms.

Through inevitability, preconceptions, reciprocating aesthetics and designs, and existing science fiction fantasies, we find ourselves in a context where the future is increasingly foreclosed. I want to walk through some specific tools, strategies, and techniques used to address this. Understanding this is crucial for designers and practitioners to challenge their own assumptions about the future and how they might be embedding their preconceptions into their designs.

If you’re engaging in critical practice, you can do both: create commercial products and be critical. How do you raise people’s awareness of these assumptions? How do you challenge them using design as a language? I’ll cover a few different sections and try to go through them quickly.

Through the Invention of Use

As the title of both this talk and my PhD indicate, I approach technology from a social constructivist position. This idea suggests that technologies don’t pre-exist or emerge autonomously; they are products of social dynamics. Technologies emerge because there is a social context for them. They are products of hopes, fears, aspirations, coincidences, and various other factors.

This theory was established by Trevor Pinch and Wiebe Bijker in the 1980s. They argued that existing theories of technology didn’t account for politics and society. Instead, they focused on innovation, military funding, and other factors, but not on how people are inherently unpredictable and do unexpected things with technology.

The example they drew on in their original paper, which they later expanded, was the rubber air bicycle tire. It was invented in 1896, or maybe 1886 (I may have the date wrong, apologies) by Dunlop, now famous for Dunlop Tyres. Speaking of technologies that were “out of the bottle,” bicycles at the time were incredibly risky. They usually had wooden wheels, sometimes lined with steel or iron, making them very uncomfortable and with almost no grip, thus very dangerous. However, this danger and riskiness made them masculine.

In a European context, cycling was associated with masculinity, speed, power, confidence, and risk. It was dangerous, especially since there were no traffic laws at the time, leading to street races and other risky activities. Dunlop, a vulcanized rubber importer for machinery, invented the rubber air tire for the safety of his son, he was concerned that he might hurt himself while riding his bike.

Initially, the rubber air tire was widely derided. People thought it was comical to put rubber air tires on a bicycle because bicycles were meant to be masculine and risky. There are great newspaper clippings from the time showing crowds of women pointing and laughing at the rubber air bicycle tire.

But Dunlop realised that the rubber air tire also made bicycles faster due to better grip. He started sponsoring people to enter bike races with his tires, paying them to do so. By doing this, he shifted the perception of the technology from being about safety to being about speed. Because it was about speed, it conformed to the preconceptions people had about bicycles—speed, power, and masculinity. He managed to change the technology from something seen as feminine or juvenile to something associated with masculine pursuits like bike racing.

The reason this example is discussed is that there was no pre-existing problem that the air tire solved. It was ready to fit into whatever niche society was ready for it to occupy. There might not have been a niche for it, and it could have failed. We could still be riding around on wooden and steel wheels, for all we know.

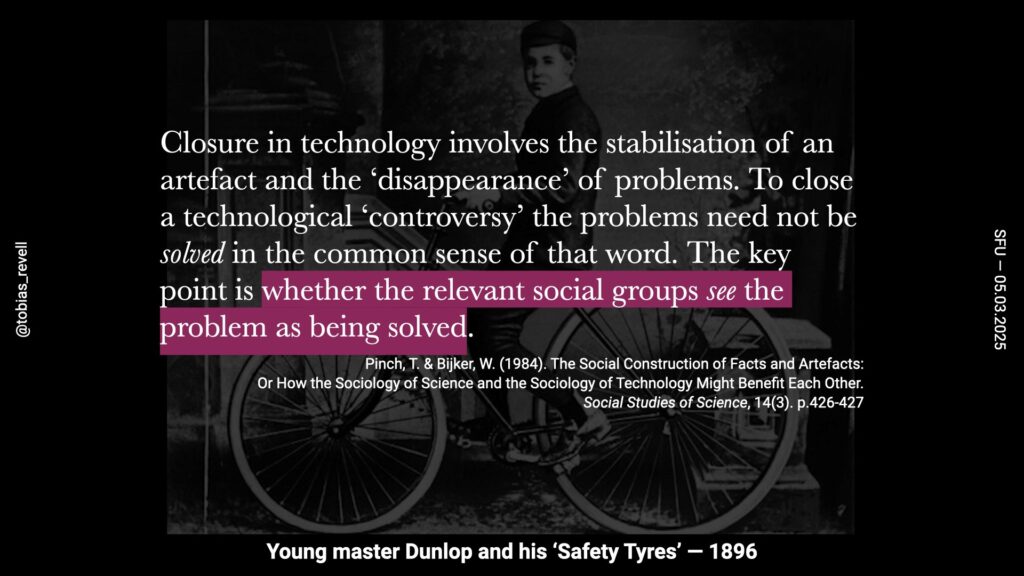

Pinch and Bijker argue that “closure” in technology refers to the popular acceptance and understanding of a technology and what it does…

A contemporary example would be the smartphone. When it was invented in the early 2000s, it was initially marketed to business people, particularly businessmen, as a productivity and efficiency tool. Later, with the accidental invention of text-based communication, it became a social device. It took on a new meaning and became immensely popular, as we know.

And now of course, so-called generative AI faces the same problem: You’ve created this machine that can do an incredible thing, but no one knows what to do with it other than make pretty pictures.

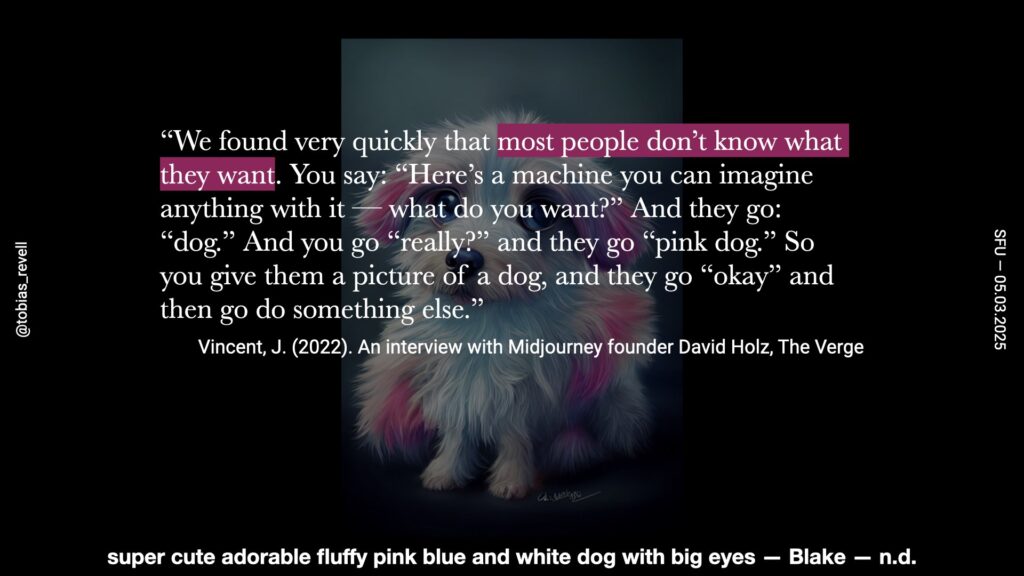

David Holz, the founder of Midjourney and previously Leap Motion, observed that most people don’t know what they want…

This was during the early stages of testing, long before the ChatGPT moment, when the technology was trying to find its place in the world more gradually. There wasn’t a clear position for it. In AI, there have been decades of storytelling about what this technology can do.

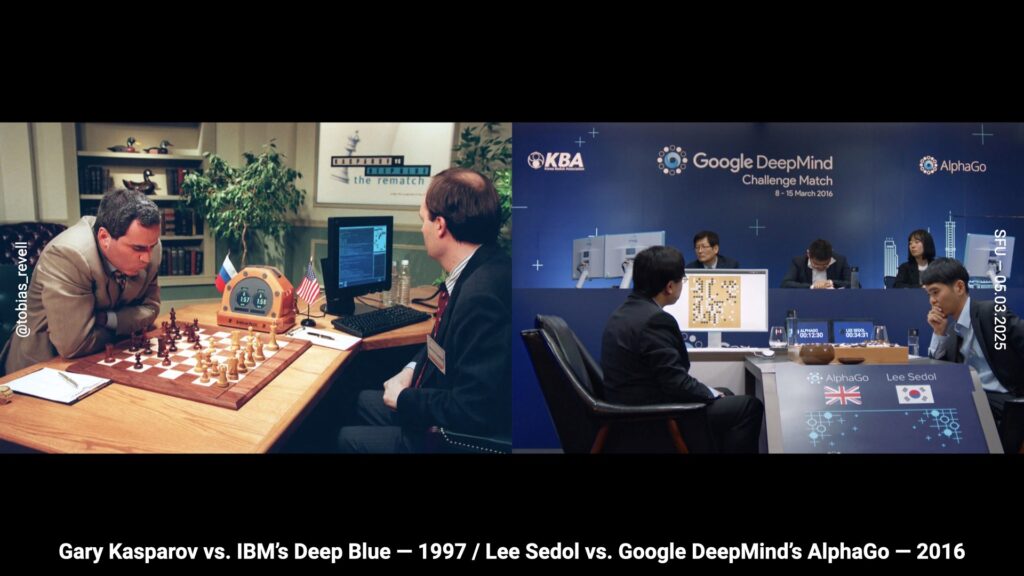

We have, for instance, Gary Kasparov’s famous loss to IBM’s Deep Blue in 1997, paralleled with Lee Sedol’s loss to AlphaGo, Google DeepMind’s machine learning system. These events are intentionally designed to sit next to each other. Even in the layout of the match, the way they’re reported, and the way they’re mythologized, they are meant to indicate a path of progress.

Demis Hassabis and the other DeepMind folks talk about the fact that Go is much more complicated and advanced. However, they frame the stakes and jeopardy of these events in much the same way, constructing the idea that they are on a path of progress and trying to achieve something significant.

Incidentally, Nathan Ensmenger discusses why games are so central to the development of artificial intelligence, describing it as a distraction. Many computer scientists acknowledge that working with games isn’t particularly useful for science. Ensmenger says…

A lot of the reporting after AlphaGo, even from DeepMind, admitted that they had created a computer very good at playing Go, but not much else. So, you have to invent uses for it.

If you watch documentaries about these topics, as I have during my studies, you’ll notice a recurring theme. There’s always a point where they say, “Okay, we’ve made a machine that can play Go very well,” in AlphaGo’s case, “and that will obviously lead to breakthroughs in science and medicine.” The logic is that if a machine can play Go, it must be capable of being a brilliant scientist. Similarly, IBM’s Watson, the machine that won Jeopardy, is often discussed in terms of solving problems that people really care about, now that it’s proven to be very good at playing games.

This is known as the “first step fallacy.” The assumption is that if a machine can do one thing well, it can therefore do everything else well. This assumption is deeply rooted in social beliefs, particularly in the West, where people who excel at games like chess and Go are often seen as highly virtuosic in various fields. Chess, for example, is associated with wisdom, brilliant political and literary achievements, military strategy, and more. By drawing this equivalence, the belief is that if something is really good at chess, it must be good at everything else.

However, we know this isn’t true scientifically. Chess and Go, while incredibly complicated, are still limited frames. They are not as complex as having a meaningful emotional relationship with another person, which is much more complicated.

What I’ve been tracking recently, which I’m really interested in, is the dialectic between design and technology. There’s a whole discussion to be had about automating games and creativity. It’s arguable that there’s an intention to demonstrate uniquely human capabilities, like creativity, virtuosity, game playing, music making, and writing. If you can compute these, you can extend the logic that anything is computable.

There’s a dialectic where there’s an aim to automate creativity to some degree, such as in designers. Equally, there’s the brilliant Figma campaign appealing to designers to tell Figma what AI is for, which I find amusing. They’re not the only ones doing this. They’re not even pretending to know what AI is for or what problem it solves. They’re trying to unload the burden of inventing that use onto you as the user while convincing you to pay for it. This is all about inventing use to secure an imaginary of AI and how it’s going to make you more powerful in different ways.

Through the Spectacle of Progress

Another dimension is the idea of spectacle—creating big spectacles of technological performance and virtuosity. Collins refers to these as “epideictic displays.” They are displays of technological prowess that appear to be scientific because they are dressed up as science. In other words, they are didactic science, but in reality, they are performances.

This is not a new problem for contemporary technology. It was a massive controversy at the beginning of scientific rationalism in the 1780s. This worldview emerged from European universities, suggesting that everything is reducible to component parts that can be documented, organised, and controlled. During this time, we saw the invention of encyclopaedias and natural atlases, which went hand in hand with colonialism, the gathering of species, and the classification of races and species.

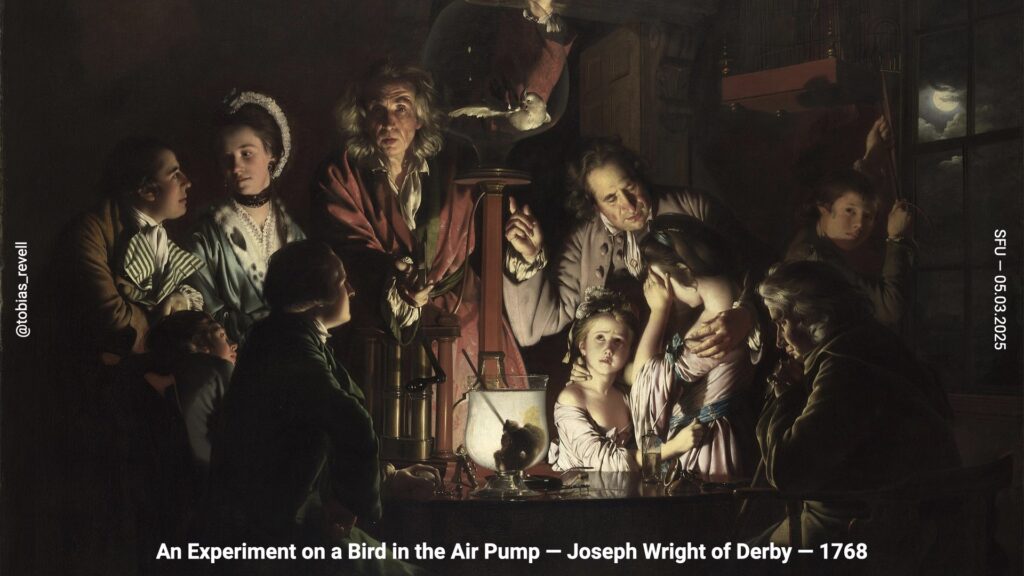

There was also a huge public interest in science. Science became cool for the first time since the Greeks, perhaps. Public performances of science became popular, where people would do things like put a bird in an air pump. In London, you could watch autopsies at the Royal College of Surgeons. These performances were presented as scientific processes, but they were purely theatrical because the audience lacked the scientific training to critique what they were seeing.

Hobbes critiqued this, saying it was not real science but theatre masquerading as science. A famous example is the work of Mesmer and Galvani, who claimed that electricity could bring people back to life because they could make frog legs twitch with electric fields. The audience couldn’t understand the fundamental science, but the excitement of seeing it turned it into a spectacle. AI continues in this lineage of epideictic displays of apparent virtuosity.

This is an example I study and talk about frequently: the appearance of Aida, claimed to be the first AI artist, at the House of Lords Select Committee in the UK in October 2022. The committee, focused on digital creativity or the future of creativity, conducted interviews and hearings to put together a proposal for the government. Aida’s appearance was touted in the press as the first appearance of a robot in a legislative setting, making headlines in the Guardian and other news outlets.

During the 22-minute hearing, Aida answered generic questions about creativity, arts, and AI. It turns out that all of Aida’s answers were pre-recorded due to the technology’s unreliability. Aida even broke down during the hearing, with its eyes losing focus and wandering around the room. The answers it gave were prosaic and generic, offering little insight.

The event is fascinating to study because the press coverage and excitement around it indicate that the hearing’s substance was less important than the fact of the hearing itself. The government had recently released an AI strategy, investing heavily in keeping companies like DeepMind in the UK and setting up a new tech quarter in North London. This performance was crucial for the government to appear future-facing.

For Aidan Meller, the inventor of Aida, it was an important opportunity to showcase his technology. Aida is presented as feminine, juvenile, and a prototype, which are all design choices. The exposed robotic arms emphasise its prototype status, making the audience more forgiving. The feminine presentation leads legislators to refer to Aida as “her” and “she,” despite their initial attempts to avoid gendered language. The juvenile presentation makes Aida appear youthful, playful, and forgiving of its flaws.

These design choices benefit the actors involved. The House of Lords and the government have the power to direct press attention and shape the agenda, promoting the idea of the UK as a technologically innovative country engaged in the arts through technology. Aidan Meller benefits from increased press coverage of his machine.

Interestingly, the company that built Aida typically makes animatronics for film. When tasked with creating a robot artist, they initially designed the most efficient robotic arm possible. However, Meller insisted it needed to look like a person, despite the human body not being the best design for an artist. This decision was another design choice, prioritizing form over function.

There is much to explore in how these stories about technology are framed as progressive.

This example comes from the AlphaGo film. The film was made about the match against Lee Sedol by DeepMind. To be clear, DeepMind commissioned, made, and released this film, so it’s naturally promoting themselves. It’s a David and Goliath story, with DeepMind presenting the challenge as nearly impossible.

Demis Hassabis talks about how Go has more possible moves than there are atoms in the universe, emphasising the complexity and scale of the challenge. The film features tense string music and dramatic scenes, such as Lee Sedol going out for a cigarette, captured with a long lens and minor chord violins. The film ends on a joyful note, suggesting that this amazing machine will make the world a better place, with scenes of people walking through fields and talking about a brighter future for their children. The narrative doesn’t quite track for me, but it’s compelling.

What’s particularly interesting is the use of enchantment, a phenomenon in social sciences where something—be it art, technology, music, or a game—appears so compelling and enriching that it seems to exceed human creativity. Alfred Gell discusses this idea in the context of religious art, where viewers perceive the art as spiritually guided due to its technical and creative advancement.

Throughout the film, Go is presented as enchanted, given incredible weight due to its complexity and the lifetime it takes to master. Millions of people follow grandmasters, adding to its mystique. So, when the computer wins, Go is disenchanted; reduced to math and rules, losing its supernatural properties. At the end of the film, AI is then enchanted, becoming the gestalt entity because it has beaten Go.

Another crucial aspect is charisma. Technologies require charismatic narratives and people to sell them, as many social scientists have noted. Charisma is a powerful yet underrated element in promoting technological advancements.

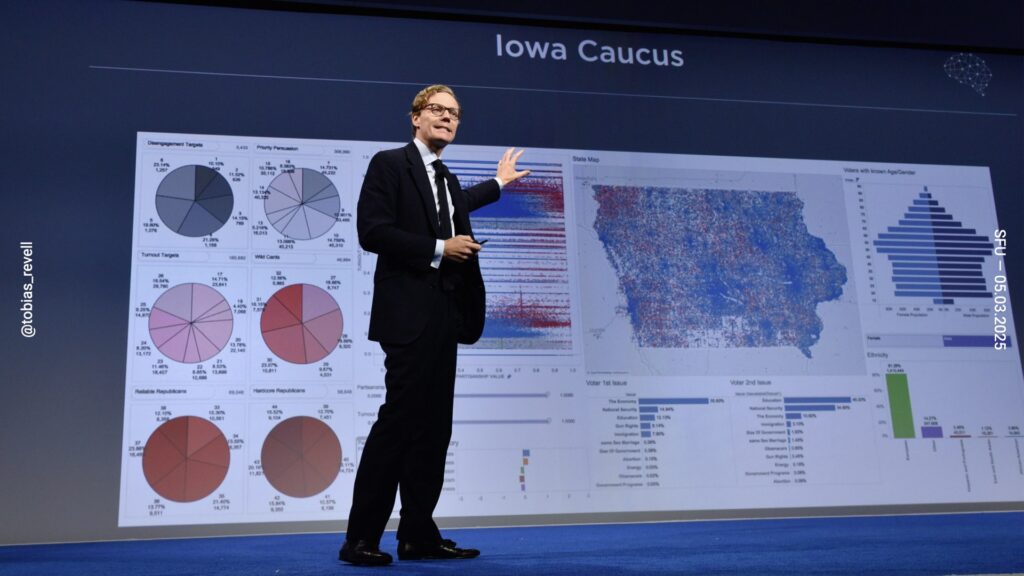

This is Alexander Nix, who was the head of Cambridge Analytica. They were guilty of stealing data from around 8 million Facebook profiles, claiming they could use AI to fix elections, which they couldn’t. MIT researchers discovered that Cambridge Analytica didn’t really have any AI; they just had a lot of data and some Microsoft Excel spreadsheets.

Nix is very charismatic. As a public school guy associated with Cambridge University and he had “Cambridge” in the title of his company. He would stride across the stage, confidently proclaiming success in front of graphs that were incomprehensible to everyone. This charisma was a crucial part of the story.

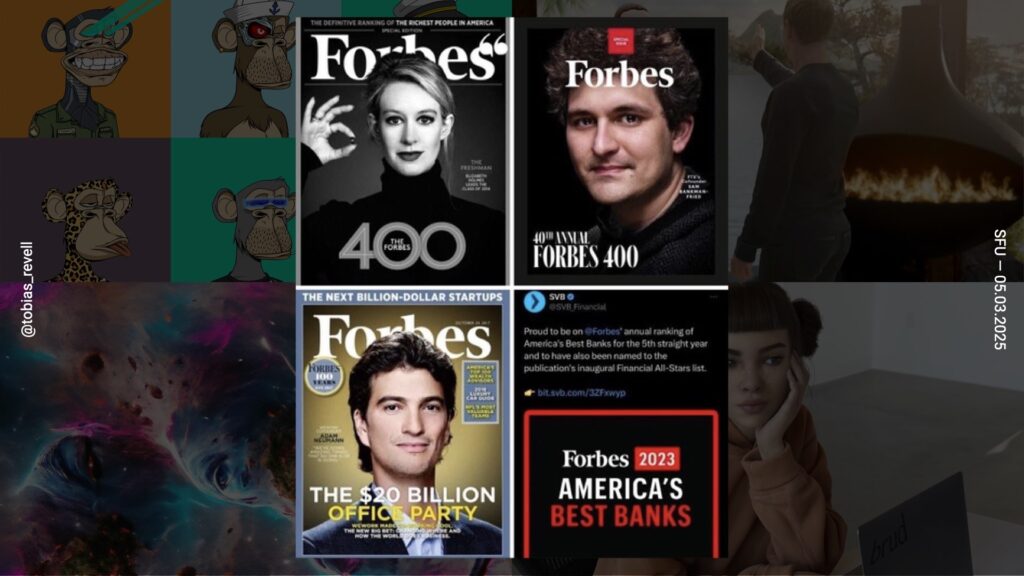

We see this repeated time and time again in technology. Almost every week, for anyone who follows Molly White’s amazing newsletter, there’s a new story about a supposed genius exposed as a scam artist or fraud. Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos claimed to have invented a device that could perform a blood test with a single prick. Sam Bankman-Fried was involved in a crypto scam. The guy who collapsed WeWork, and then Silicon Valley Bank, which was found to be insolvent once the news got out, all feature as charismatic leaders within the field of technology.

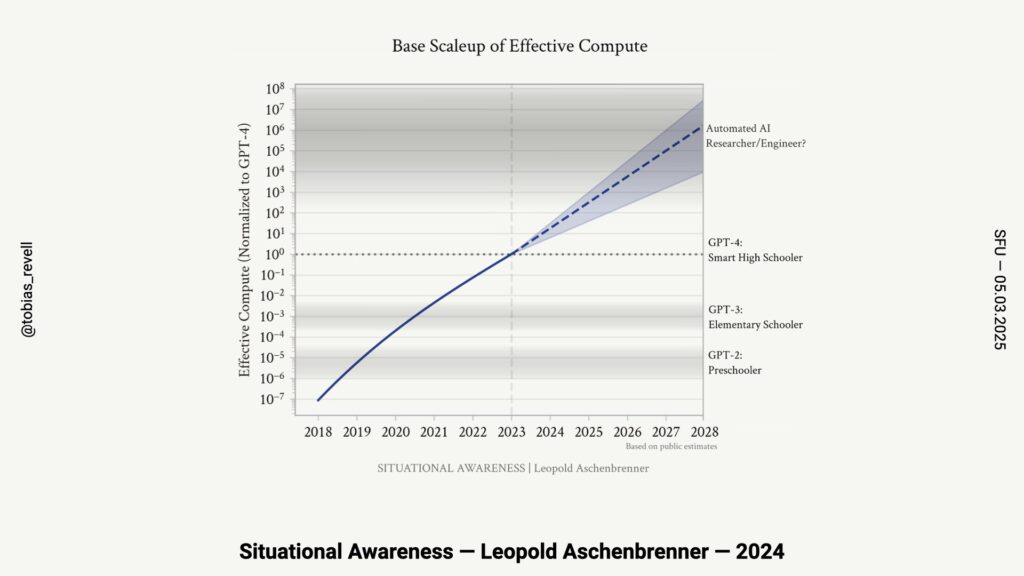

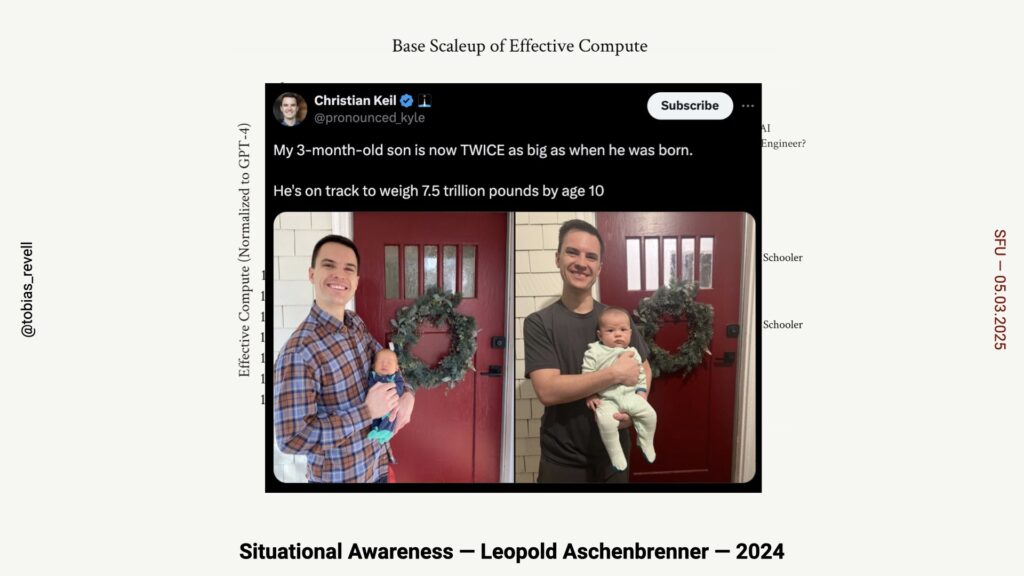

Another aspect of progress that I’m currently exploring is the “line goes up” idea. Whenever there’s bullish reporting on technology or anything associated with progress, it usually involves a graph that looks like this in one way or another. These graphs are often associated with foresight and futures, particularly the S curve, a standard model of how a technology proliferates and becomes profitable in society. While the S curve tends to work, it can be scaled to any timeframe—100 years or a week—and still appear valid. This makes it unreliable in an objective sense.

Similarly, charts from a famous blog post by a slightly discredited former OpenAI researcher discuss how close we are to AGI (artificial general intelligence), or human-level capability. Many people make this claim frequently, but it’s based on flawed logic. The assumption is that if the line goes up for a certain period, it will continue to go up indefinitely, which is never the case. We live in a zero-sum world with limited resources, so lines don’t go up forever.

As prominent mathematicians might point out.

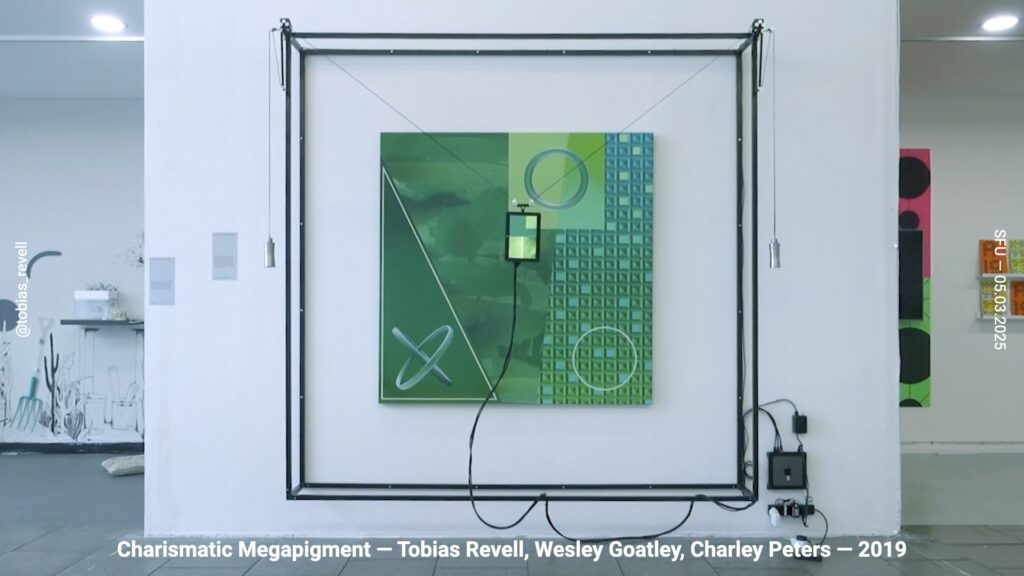

This is a project from 2019 called Charismatic Megapigment that I did with my very good friend and collaborator, Wesley Goatley, and the artist, Charley Peters. At the time, deep learning was definitely a thing, and people were talking about machine learning and deep learning, particularly in robotics and autonomous vehicles rather than generative AI. Most of the machine learning happening was discriminative rather than generative.

We created Charismatic Megapigment by taking one of Charley’s paintings who is a formative painter, meaning she goes with her gut and what feels good aesthetically. We then built a machine that tracks randomly over the front of her painting with a camera on the back. As it tracks, it uses a nearest-neighbor algorithm to find corresponding images from Google, saving them to a bank. The project aimed to create a spectacle with no inherent meaning. The machine’s actions didn’t have a particular outcome or desired effect; it was about exposing the way these systems work and highlighting that their functioning has no inherent meaning—only what we choose to do with it and how we interpret and use it later.

At the end of the process, we had a database of about 125,000 images drawn from Google Images. Many of these images concerned sustainability statements, as it was near the time when various companies and organisations were announcing climate emergencies. This exercise built an aesthetic representation of what contemporary internet society thought “green” was at that time. It also demonstrated that these systems are reflective of each other. If you’re training a machine learning system on images of green, you’re likely training it on images of sustainability statements from corporate websites.

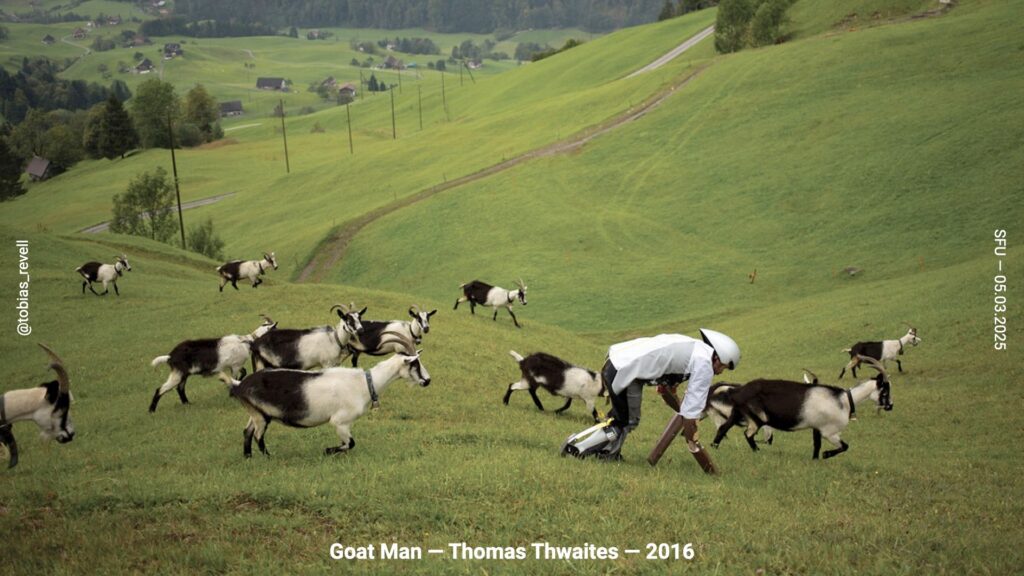

A project by someone else that I like, and it’s a bit of a wild card, is Goat Man by Thomas Thwaites. This project challenges the assumptions baked into technologies as we critique them. Thwaites was interested in transhumanism, body modification, and the prosthetics world, which focuses on making people stronger, faster, or modifying the body to stay up longer or digest faster.

Thwaites asked, “What if your aspiration isn’t to be a faster, more productive person, but to be a goat?” What if all you want in life is to sit around on a hillside eating grass and grazing? This provocative and funny challenge questions the mainstream imaginary of technology’s purpose. Instead of prioritizing speed, productivity, and efficiency, why not enable people to live out an abstract fantasy of being a goat?

Thwaites documents his projects meticulously. He interviews experts, talks to scientists, makes his own pieces, and learns about the processes and sciences involved. He builds a body of research reflected in the exhibitable work he produces. He actually spent about 18 hours living as a goat before his back gave out, and he made friends with some goats during the process.

This isn’t a talk about design research, but if it were, Goat Man is an excellent example of the idea that the design artifact itself is the research. You don’t have to do a bunch of design research and then write a paper; instantiating the research into a thing is the design research.

This is an amazing project that I’ve written about extensively and love. It challenges two concepts we’ve discussed: the personification of AI, as seen in Aida, and the use of spectacle. Stephanie Dinkins has been having conversations with a machine called Bina48 for several years. Bina48 is an animatronic robot based on a real person named Bina Aspen, a philanthropist.

Dinkins’ project explores how a team of mostly white engineers tried to capture and represent the experience of a Black woman in this AI and animatronic machine. She engages in conversations with Bina48, delving into its life experiences, history, and upbringing. What’s fascinating is how Dinkins treats the machine purely as a machine. She consciously maintains a machine-like relationship, staring directly at it and leaving long, awkward pauses while asking questions. This makes the audience uncomfortable, as we subconsciously personify the machine despite knowing it’s a robot.

This brilliant piece of critical practice challenges our baked-in assumptions about machines, personification, and anthropomorphization through performance and film. Dinkins has been working on this project for a long time, and it’s an incredible piece of performance and critique. Similar to Tom Thwaites’ work, it also exposes the background and story of the technology’s construction—who’s funding it, why they’re funding it, and the motivations behind the design.

Through Myths and Pre-Expectations

I mentioned the Haunted Machines project at the beginning. This started about 10 years ago when Natalie Kane, a curator of digital at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and I became very interested in why there was a rhetoric and language of magic, myth, and the occult occurring around technology, particularly smart technologies and connected technologies at the time.

In 2014 and 2015, there was a growing public awareness of machine learning, which became more prominent around 2015 and 2016 with the emergence of DeepDream. Apple also contributed to this awareness by talking about the “magic” of Mini and similar technologies. There’s some excellent scholarship on this topic, which is a significant part of my PhD work.This ties back to enchantment and Anthony Enns’ discussion on psychotechnologies…

We mentioned earlier Sun-Ha Hong’s work on excusing self-driving car crashes by promising a future without road accidents. Another example is Sam Altman’s Intelligence Age Manifesto, where he openly discusses the challenges of transitioning to artificial general intelligence. However, he concludes with grand promises of immortality, the end of climate change, and the resolution of all scientific problems, playing into these fantasies.

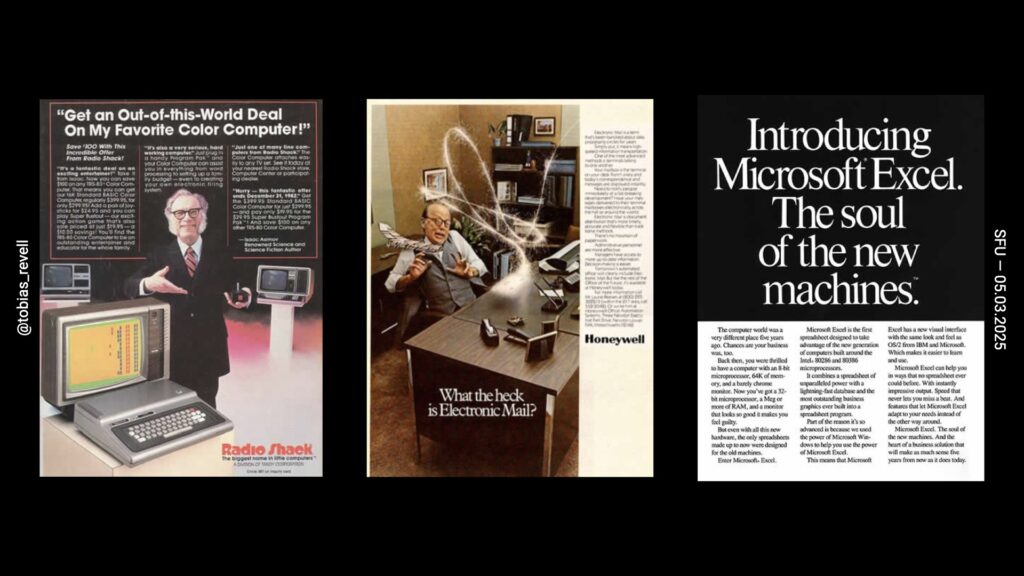

Magic has long been one of those fantasies embedded in technology, especially since the advent of the PC. The PC was the first object to move into homes without an apparent design use. Before the PC, consumer electronics like microwaves, toasters, fridges, and washing machines had clear functions. The PC, however, was an amorphous gray box capable of many things, with its capabilities constantly evolving. By the late 1980s, PCs could connect to the Internet in some places, making it hard to define their purpose.

To give the PC meaning, it was often associated with fantasy. Isaac Asimov described it as an alien object, linking it to popular sci-fi like Star Trek and Star Wars, or Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Email was presented as a poltergeist, and Excel was described as the soul or spiritual dimension of machines. These fantastical associations helped embed the idea of magic in technology.

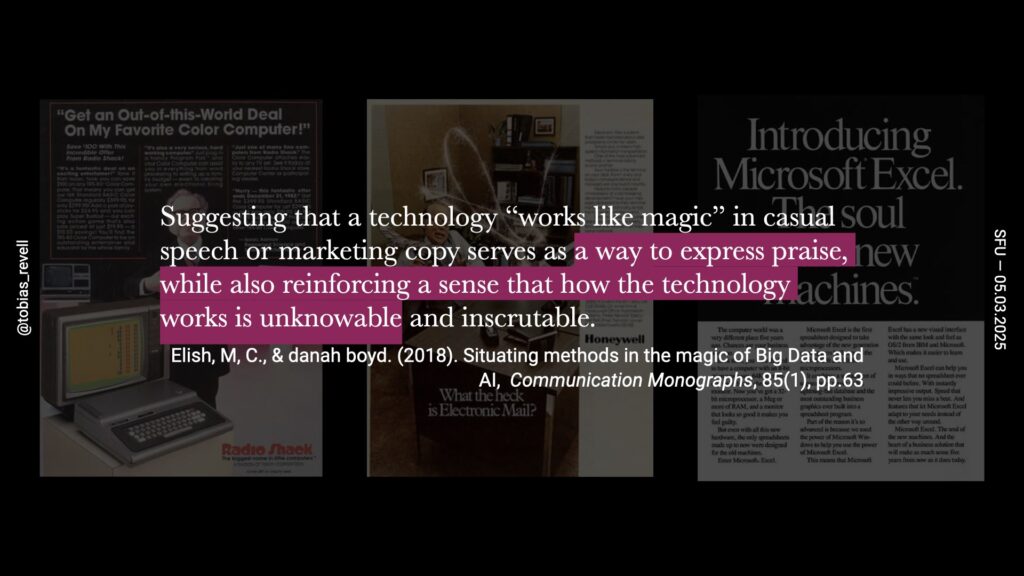

MC Elish and Danah Boyd discuss this and say…

In other words, magic does two things: it makes technology appear magical, beyond human comprehension, enchanting it with gestalt properties; and it emphasises its complexity, suggesting that it’s too intricate to understand. This is often seen with charismatic figures in technology. For example, Bill Gates was described as the “Wizard behind the PC” on a cover of Time in the 1980s, and Steve Jobs was frequently called a magician. People who are deeply into technology are often referred to as evangelists, implying that understanding high technology grants secret power over it.

This magical rhetoric is also present in discussions about prompt engineers in generative AI, who are sometimes described in magical or spiritual terms. The use of magic and myth is a specific way stories are told about technology, and it is embodied in visual and design culture in various ways.

So, not only the rhetoric and vernacular but also the visuals often accompany them. For example, a Google image search for “artificial intelligence” reveals an aesthetic homogeneity. They’re all blue, featuring androgynous robotic machines often in a Rodin pose, surrounded by blue light. There’s a reason why it’s blue now and not green, as it was in the 1980s. This change is related to dyes and film, as explained in a 99% Invisible episode.

This aesthetic is replicated in cinema, where there’s an association between the representation of magic and technology. Both share a similar aesthetic homogeneity, often involving hands, which are likely featured because they symbolize power. This imagery is reminiscent of Michelangelo’s painting with God and Adam touching fingers.

There’s usually a focus on big data or something similar. This aesthetic homogeneity is pervasive in culture, but people are becoming more aware of it. The BBC has been working on a project called Better Images of AI, collaborating with artists to create more representative and descriptive images of AI. Mozilla has a similar project, and even DeepMind has resident artists working on better stock images of AI.

Science fiction plays a huge role in the construction of technology and people’s perception of it from all dimensions. There are three main actors at play: science fiction writers and producers, the public who consume and engage with this media, and investors in real technology who watch these films and shows. Importantly, as many scholars have pointed out, people who make AI also watch science fiction. They are inspired by it and often try to replicate the technologies they see.

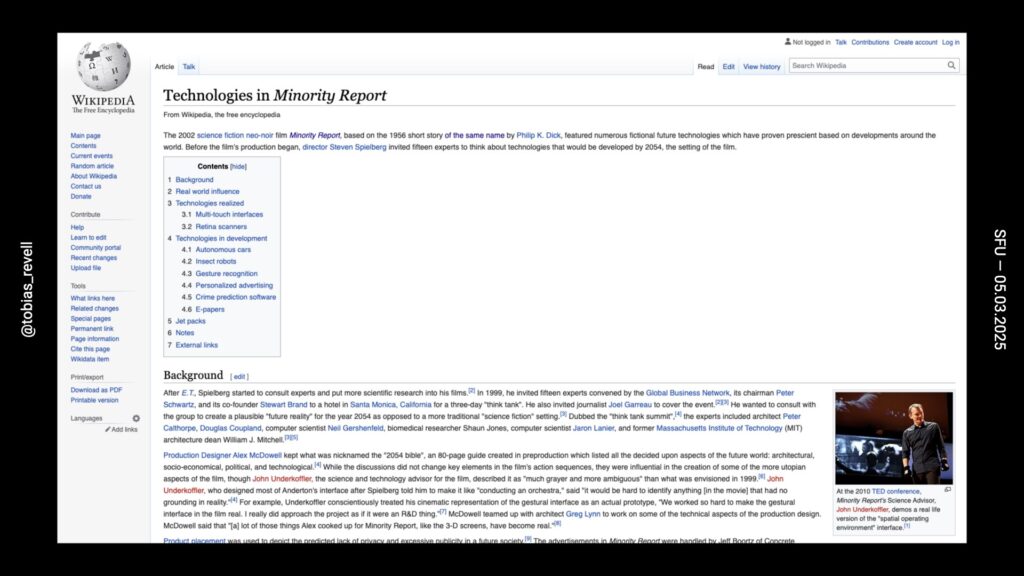

One of the most well-studied examples of this is Minority Report from 2001. David Kirby has written extensively about the impact of this film on technological development. There must be tens of billions of dollars invested in technology purely on the back of Minority Report. The film was designed by Alexander McDowell. He put a huge amount of effort into designing technologies from Philip K. Dick’s short story, written in the 1970s, long before concepts like facial recognition, eyeball tracking, augmented reality, predictive AI, and autonomous vehicles were even conceived.

McDowell’s designs were so influential that they have had a significant impact on the reality of technology. There’s an entire Wikipedia page dedicated to the technologies in Minority Report, and the film is frequently referenced in press coverage, especially around consumer electronics shows.

One fascinating aspect is the gestural interface, the first time such an interface was shown in a film. Tom Cruise’s character uses gloves to grab files, objects, videos, images, and text, moving them around with his hands. This was a project by John Underkoffler at MIT Media Lab. McDowell, being a thorough researcher, consulted with many scientists and technologists to incorporate state-of-the-art technology into his designs.

David Kirby notes that…

For example, there’s a glitch in the film where Tom Cruise’s character is moving windows around, and Colin Farrell’s character goes to shake his hand, causing all the windows to jump towards Farrell’s hand. Cruise has to push him away and pull the windows back. Details like this make the technology feel real because they mimic the glitches we experience in collaborative documents.

McDowell and Underkoffler are brilliant at incorporating everyday diegetic moments, making the technology feel more authentic.

But there’s a problem with this feeling of it being so real and so convincing as a future and the reason it has inspired billions of dollars of investment. As Frederick Jameson discusses the problem with science fiction foreclosing futures. He says…

This idea is groundbreaking. These visions of the future, whether from science fiction, press releases, or Aidan Meller’s robot in the House of Lords, aren’t about presenting what the future might be. They’re about saying that we are in the past of a future that’s already coming. This future is inevitable, pre-decided, and we just happen to be in its past.

Jameson suggests that these images are overwhelming and designed to convince us that this future already exists and is ready to go. We’re just in the past of it, and it’s not quite here yet. This ties into the story of inevitability. Additionally, science fiction draws these equivalences, reinforcing the idea of a predetermined future.

To go back to Aida, the staging of Aida in the House of Lords would not have been effective if people weren’t familiar with this trope from films like Bicentennial Man by Chris Columbus. In the film, the android character, played by Robin Williams, appears before a government organization and is forced to profess his humanity. These pre-expectations are crucial; without them, people wouldn’t know how to interpret Aida’s presence in the House of Lords. This setup is common in science fiction, with numerous examples from Star Trek and other media reinforcing the idea that such events are inevitable.

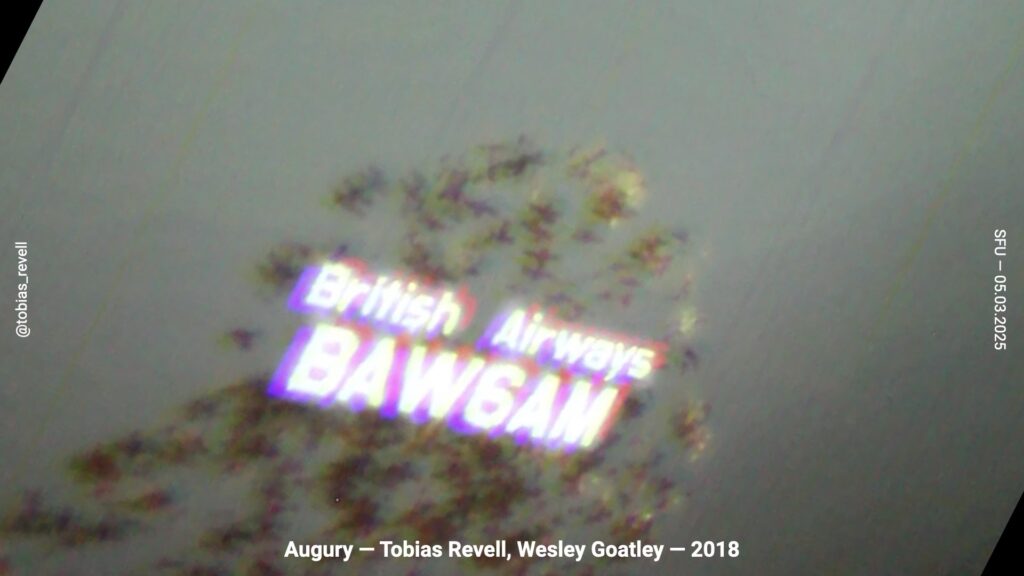

So what can critical practitioners do to challenge and reveal these tropes and to restage or reframe AI? This is a project called Augury that I did with Wesley Goatley, my friend and collaborator. We aimed to question the power positions between how technologies are presented as magical and inevitable, and how they’re physically manifested and positioned. Augury is a machine learning system we built.

Augury is an ancient Greek and Roman divination practice where people tried to predict the future from the flight patterns of birds or, in some cases, from the entrails of birds. For example, if the birds were flying east, it might be interpreted as a sign from Zeus to go to war, or whatever.

For six months, we recorded the flight trajectories, positions, altitudes, and flight numbers of planes over the gallery we were working in. This data, called ADS-B, is freely available and easy to gather, at least in the UK. We also collected the latest tweet about the future from within a 50-mile radius of the gallery every five minutes.

We then trained a machine learning system using sequence-to-sequence learning, similar to how translation systems are trained. The system analysed plane positions and tweets about the future to generate new predictions based on the current positions of planes. Of course, these predictions were complete nonsense and didn’t make any sense.

At the time, Amazon Web Services was promoting the magic of their machine learning system, using terms like “magical” to describe its power and function. We wanted people to be more aware of their physical relationship with the machine. As you can see, people had to lie down to interact with it. Unlike typical interfaces or monitors, it required users to prostrate themselves before it to work it. We were poking fun at some metaphors and being a bit absurd.

Projects I’ve done in this space are also about figuring out the technology itself. I’m not a programmer or an AI expert, so I learn as I go. This process forces me to confront and question the decisions that computer scientists, programmers, or product developers might make. It’s a critical process of reflecting on the assumptions, predispositions, and templates baked into software packages and how they influence behaviour.

Through Technological Normativity

The final topic in imaginaries and design is technological normativity. You’re likely familiar with the argument that generative AI has a homogenizing effect, flattening things because it’s essentially a statistical averaging machine. However, this isn’t unique to generative AI; it’s a natural product of the mass production of creativity in various forms.

I first came across this idea in 2014 through a concept called the Shazam Effect, a term coined by a journalist reflecting on a paper by a group of Spanish scientists. These scientists set out to determine if all pop music really does sound the same. You’ve probably heard someone say, “All music sounds the same these days.” They wanted to find out if this was true.

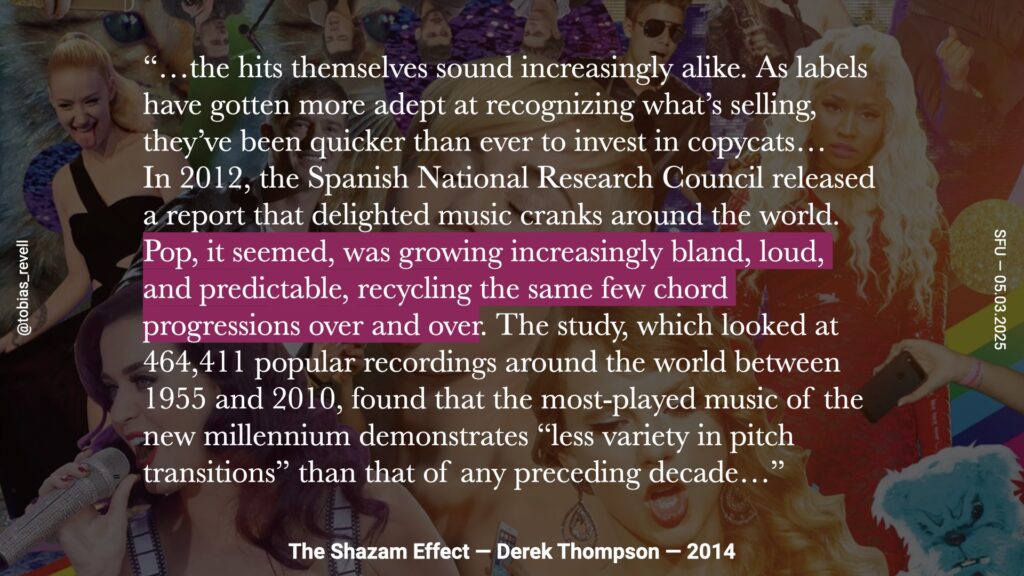

The researchers reviewed the top 50 hits of the last 100 years, analyzing their length, timbre, chord progressions, speeds, and other characteristics. They aimed to see if pop music was indeed becoming more homogeneous. They found that hits increasingly sound alike as record labels have become more adept at recognising what sells, leading them to invest more quickly in copycats.

The phenomenon they discovered was that, due to streaming and tools like Shazam, record companies could access vast amounts of data on what people were listening to and enjoying. This allowed them to produce more of what was popular. They could identify the preferred speed, chord progression, sound type, length, and listening habits, and then create more music that fit these criteria to maximize profits.

Bruce Sterling, the science fiction author and futurist, has a great aphorism: “What happens to musicians happens to everybody.” Essentially, musicians are often the first to be affected by future trends, and we now see this pattern replicated in other areas.

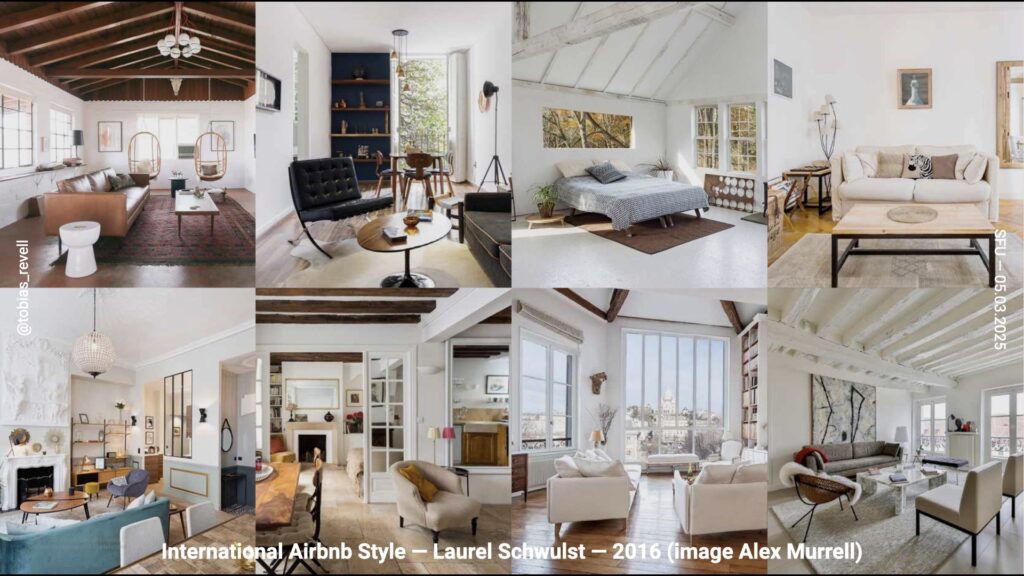

For instance, the term “international Airbnb style” was coined by Laurel Scholst. Once you have enough data on what works on Airbnb—what people click on and gravitate towards—you start to design your property to match that style. This helps attract more clicks and attention.

The same phenomenon occurs in automotive design. The “wind tunnel effect,” coined by Jim Carroll in 2015, refers to how the technologies used to model and design cars, along with the homogenization of regulations, increasingly limit what is considered a worthwhile design for speed, fuel efficiency, attractiveness, and other factors.

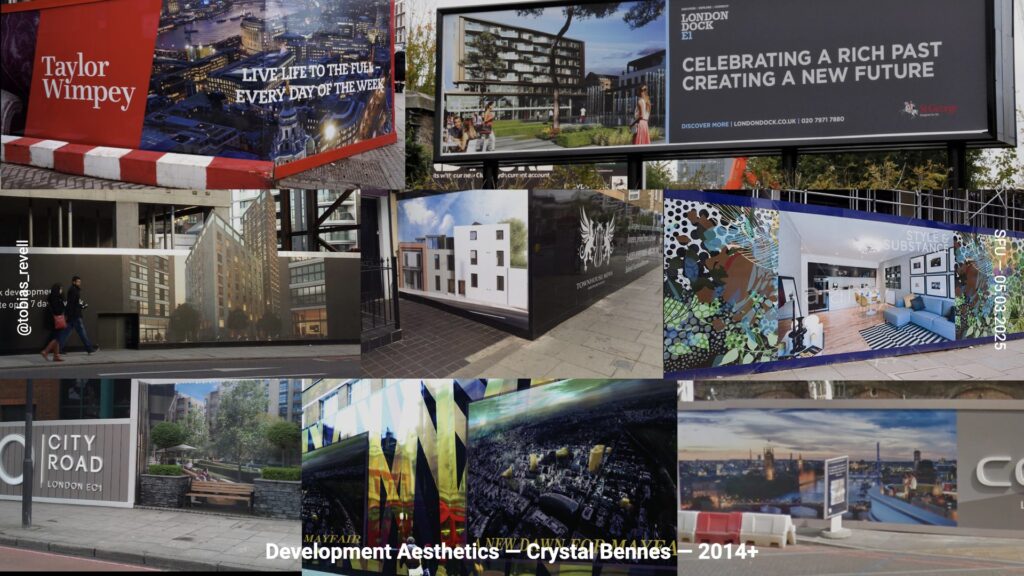

Crystal Bennes calls this phenomenon in building design “development aesthetics.” The idea is that there’s a lot of data on what appeals to developers, architects, and councils approving building projects. This leads to a homogenization of the graphic language of building and architecture, which Bennes documents in development hoardings. Many buildings look the same, accompanied by pithy statements about aspirational living in the city

These processes involve gathering vast amounts of data and understanding to replicate the average over and over again, increasing the chances of success. This results in technological normativity and a foreclosure of imagination. There are various actors in this ecosystem, including those creating visualisations, those paying for them, and the software companies producing the tools for these visualisations and music.

If people are predisposed towards glass, steel, and generic greenery, these elements become easier to produce. They become the templates, defaults, and presets baked into the software. This is similar to the “GarageBand sound” from 2007, where people reused the same drum loops and piano bits because GarageBand only had a limited selection. The same thing is happening here: presets become normalised and easier to use repeatedly, leading to a similar emerging aesthetic.

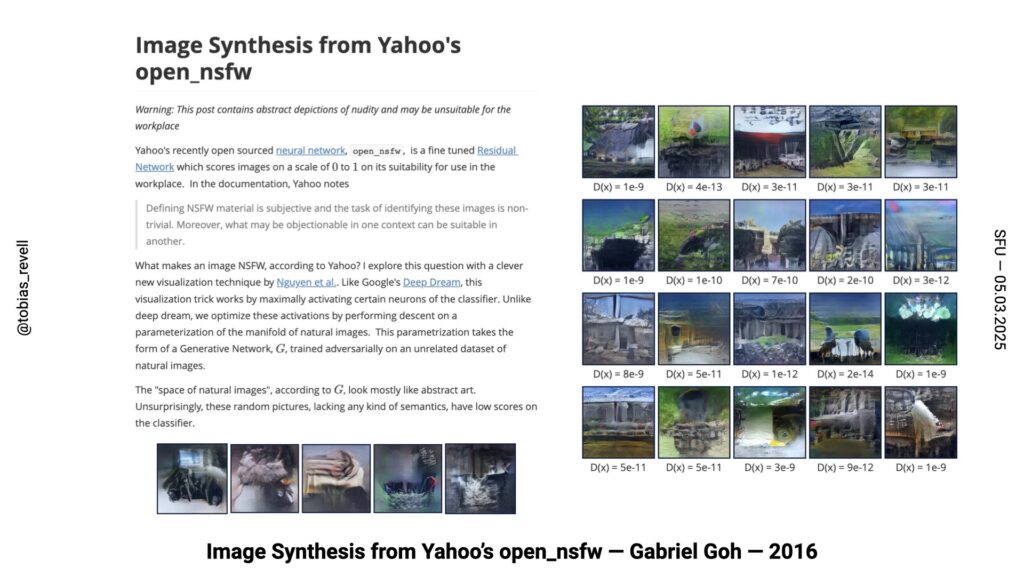

This is one of my absolute favourites for trying to reverse engineer this effect. From many years ago, in 2016, Gabriel Goh looked at Yahoo’s deep machine learning “not safe for work” (NSFW) image capture system. Yahoo developed a machine learning system to automatically detect and filter out NSFW content, such as pornographic or nude images, from their search results.

Goh took this system and reverse-engineered it to create the least NSFW image possible. He aimed to produce the most parochial, pastoral, and boring image by dialing the system all the way to the other end. The result was images that looked somewhat like landscapes, with a bit of green, blue, and sunlight, creating pleasant and serene scenes.

This project highlights the normative assumptions about what is considered “safe for work” baked into the system by the engineers. They had to define what is safe and what is not, and these definitions influenced the machine learning system’s output

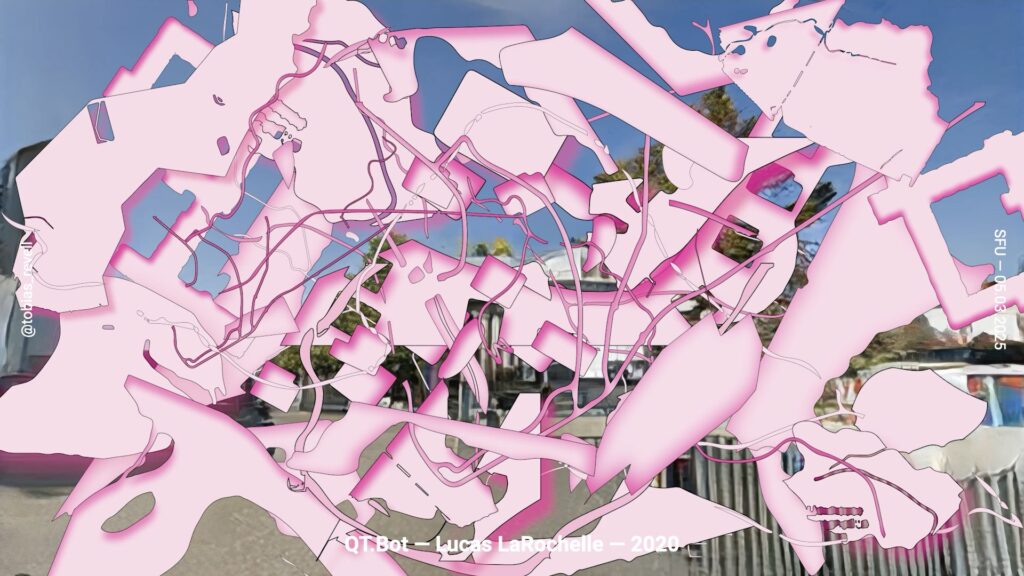

QT.Bot by Lucas La Rochelle is a great speculative yet functioning piece. La Rochelle has been running a project for many years called Queering the Map, which collects anecdotes and stories from queer folks all over the world, tagging them to the locations where they occurred. These stories range from wonderful experiences like meeting a partner to instances of homophobic abuse, encompassing tens of thousands of entries.

La Rochelle trained their own machine learning system on these stories alone, creating a chatbot infused with a vast amount of data on queer experiences. This chatbot, QT.Bot, arguably embodies an entirely queer perspective, drawing from the diverse and rich stories tagged to specific places.

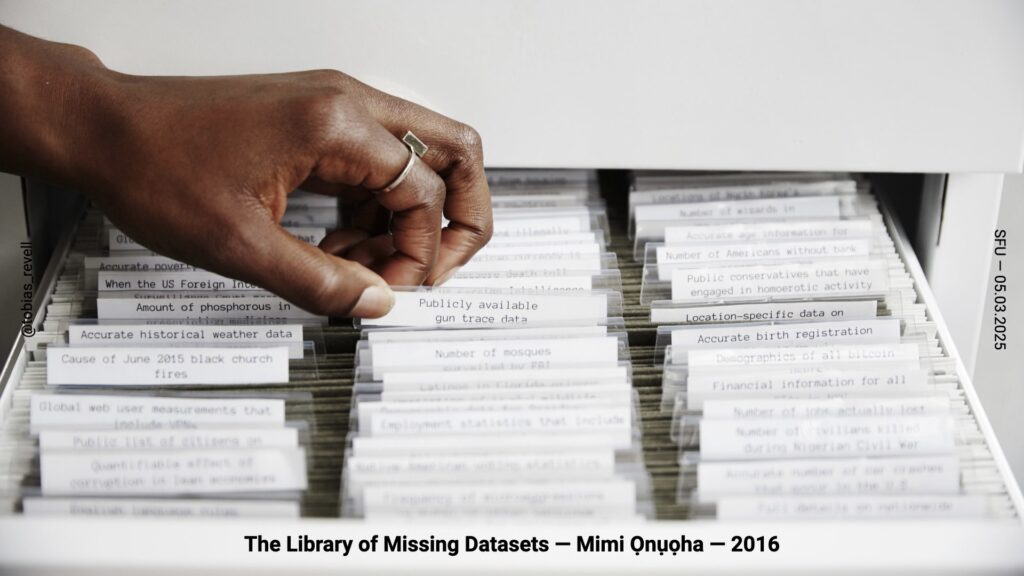

The other side of normativity is what’s left out of it. Many more qualified and smarter people have discussed the inherent biases baked into artificial intelligence and technological systems. I was lucky enough to work with Mimi Ọnụọha to exhibit one of my all-time favourite artworks, The Library of Missing Datasets. Ọnụọha documented datasets that don’t exist, such as publicly available gun trace data and the causes of death of Black men under 14—various things that aren’t kept as public records.

There’s a whole history behind this, which many others have explored. The use of data to construct the world dates back to the beginning of censuses and military censuses in Europe in the 1780s, coinciding with the growth of science. During the Napoleonic Wars, states needed to organise themselves, so they started taking censuses. This became the basis for most data gathering.

The census expanded to include yields from farms and factories, and the number of military-age people. This prioritization exercise focused on measuring the military and economic strength of the state, which became the default for constructing technologies based on data.

And that’s it. I’m just going to stop here. I wish there was some smart take away but there isn’t. This is the end of the talk.

Postscript: I had to rush through and skip some bits at the end when I realised I was creeping up to 90 minutes of continuous talking. The fact that I’ve been giving a developing version of this talk for about a year and the core thesis isn’t really moving is good because it means that the core concepts of the PhD work are solid. Obviously this talk isn’t structured like the PhD which is built around the case studies.