Last week’s post where I rambled a bit about why I found the idea of ‘preferable futures’ as a design brief so disingenuous probably needs some expanding on, some anecdotes: A couple of years ago I worked on a project with a UK government department. It was the result of four or five years planning and research on their side and we were brought in for a small slice of it to use speculative design to get some qualitative insight from public focus groups. In the middle of this, there was some very related bad press about the department and over a weekend the project ‘turned on a dime’ as the Americans would say and we had to quickly refactor the entire brief in order to not give the impression of wasting the resource invested so far but make it about something else so that it wouldn’t upset the ministers; arguably invalidating the research that went before it.

Another: We were in early stages of a big collaborative research project with a bunch of public/private subcontractors for a big Silicon Valley tech firm. This thing was moving fast and very ambitious – they wanted to roll out a new product (a pretty wild one) and wanted to do some design-led research to understand the needs of consumers and stakeholders better – and again, we were brought in to use some speculative design in order to develop some visions with said stakeholders. Suddenly, in the middle of the project, the CEO of the company has a bunch of bad press and the whole project is canned and quietly shelved. No, actually, worse than that, the company decided to shelve our bit of the project which was about building bridges, getting some buy in and feasibility for this big ambitious project and they just decided to go ahead and do it anyway because, hell; they’re a big Silicon Valley tech firm and they can just buy senators if they want, they don’t need oddball Brits doing participatory speculative design research to figure out if the project is a good idea.

I guess what I’m saying (and I am repeating myself) is that if your healthcare preferable futures project that uses speculative design doesn’t talk about the fact that the NHS is basically just politically disliked by a very particular, very powerful sector of politicians then it is white-washing the story: These people have no designerly or well-studied reason for hating public healthcare. They just believe that unprofitable public services are a sign of a degenerate, lazy society in their particular worldview – it’s just an unquestioned assumption. Equally, a speculative design for preferable climate futures would have to acknowledge that there are a lot of very powerful people and groups for whom the simple facts of climate change don’t matter when coming up against an ideology and belief in the power of the market to identify and solve problems and a general disdain for regulation.

So when I think about the role of design in the way I practice it, it is to elevate and highlight these irrational, ugly, messy things that people believe or feel and ‘have at it’ in an agonistic way. I did a lot of work on this a few years ago and got in a lot of trouble which I suppose is a good thing. I don’t think you can get everyone together to agree on a preferable future; what you can do as a designer is materialise and bring to the surface all the ways in which people are at conflict, identify some areas of concession or agreement and start to inch the whole planetary project forward a little. That’s why these ‘preferable futures’ project feel a little bit like bulldozing reality: If someone just really doesn’t like the idea of the welfare state because their dad told them it was communist then I want my design project to force them to actually articulate that belief and where it comes from rather than skip over it and sell a dreamy future that they can later ignore when they go back to parliament.

That means you have to talk about messy things like ethics and politics and ideology, which as mentioned before are, other than a few notable examples (there are probably more but there are 100 times as many self-certified UX designers doing ‘speculative design’ on LinkedIn) are not things that UX/service design generally likes to talk about because, despite the ‘critical’ turn in design from which speculative design is produced, design is still peddled by D-School design thinkers and online UX courses and LinkedIn thought leaders as a politically neutral, overwhelmingly positive, responsible growth-oriented practice. Even when the word ‘critical’ is mentioned, it’s all about extracting ‘solutions’, or just designing things further away without actually thinking about the world or how destructive design can be.

Ok, so in the style of a LinkedIn thought piece, some things to think on if you’re thinking about doing a preferable futures project:

- Is the thing you’re looking at improving actually a design problem or a political problem? (Clue: All problems are political problems)

- Since all problems are political problems, what are all the ‘irrational’ beliefs and ideologies at play? (eg. what do the tabloids say about it?)

- Would it, in fact be better to not do it? (You could, for example, work in political activism)

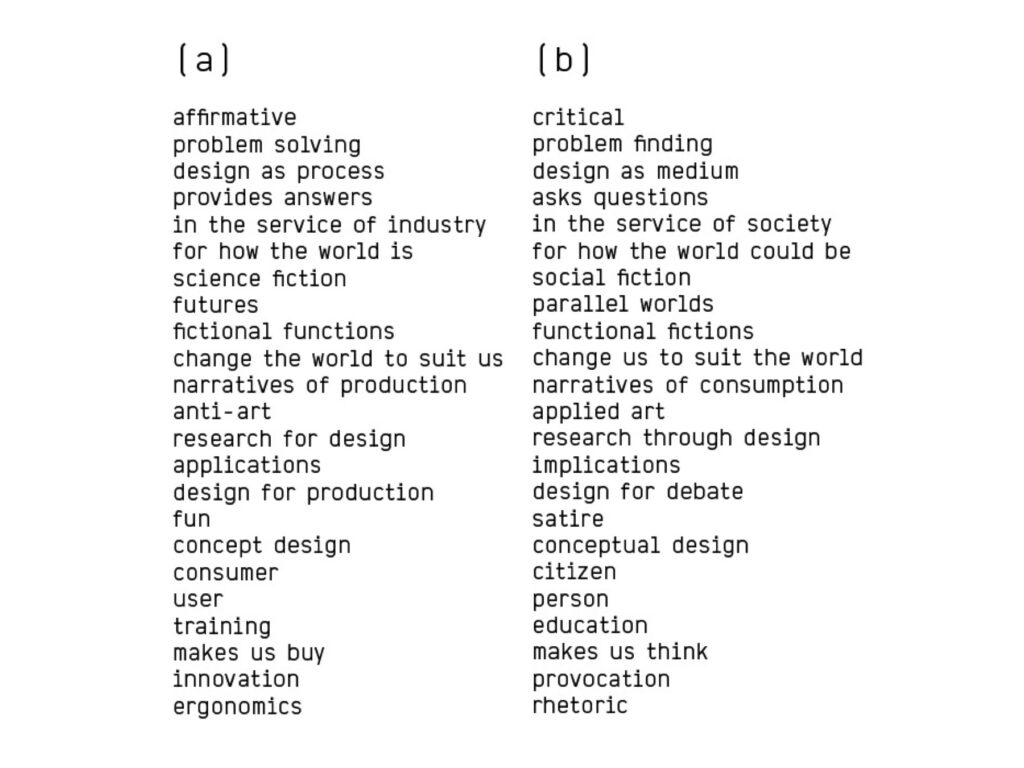

If you’re doing critical design which is critical practice then you are also in the business of critiquing the politics of design: Critical practice isn’t a way of asking better questions of your users, it’s interrogating why we have a culture that defines people as users, it’s questioning the political biases and assumptions you reinforce in designing something; the unquestioned assumptions about the way the world is and people are. Out of that notion emerges speculative design; what would a design look like that had a different set of political values and assumptions?

This is I think an important distinction; no matter what speculative design has mutated into now, it was never about just designing weird future shit because it’s cooky. It’s about examining the design and material culture we have and the biases, assumptions and politics it reinforces so that you, as a designer, can try and be more critically conscious of your design choices. Instead, somewhere along the way this all got ground to dust through a bunch of UX design sprints and now speculative design just means ‘things that haven’t been designed yet’ (devoid of speculative philosophy) and critical design is just chin-stroking app-makers; it’s sort of becoming its own bulldozing rubric of blasting out ‘preferable’ futures and weird products to drum up hype.

Short Stuff

That was ranty. It’s very frustrating all that stuff but I also try not to care, because you know, each to their own. But I also have this desperate sense of a vital and rich set of tools and ideas just being diluted and whitewashed to continue reproducing the status quo and it makes me bristle.

- Amazon Alexa is on pace to use $10bn this year as it fails (along with other voice assistants) to find a hold. According to the article, up to 25% of owners stop using them in the second week. The idea was to ‘monetise’ them but I guess people will tolerate ads when they can scroll past them or there’s a decent chunk of podcast on the other side. No-one wants to sit through an ad just to order rice or turn a light off with their voice. Azeem Azhar also made the good point that you can’t browse or explore and it relies on you holding a menu structure in your head. Imagine looking back and remembering when big tech thought it was the future just cos voice recognition had got really good.

- Short history of the techlash and Apple largely avoiding scrutiny while being eight times as big as Meta. (Not influenced by Mosk ramblings)

- The fact that Meta is almost always followed by ‘[Facebook’s parent company]’ shows you how well that whole thing is going.

- Simone looking at what the ‘Text to Everything’ revolution will do for interaction design as he suggests, this is kind of a ‘conversational UI’ v.2.0 where the more you give, the more you get and it does start to feel like quite a natural interaction, unlike voice bots. This is probably because you’re getting a direct response and feedback. There’s a crossover here with Salvaggio’s notion of treating them like game engines.

- Speaking of, they’ve launched a store for the AI-generated spoon.

- Searching with metaphors at Metaphor.Systems. J-Paul was looking at this yonks ago. It’s good but nothing new under the blah blah.

Ok, you know I love you and I’m sorry. Bye.