Do we only map things out to try and stake a claim to them? It feels like even mapping out theoretical or disciplinary stuff is just a way of staking a claim on something. That’s why a lot of folks I hugely respect out-and-out reject the idea of mapping or establishing boundaries. Anyway here’s some maps…

Mapping

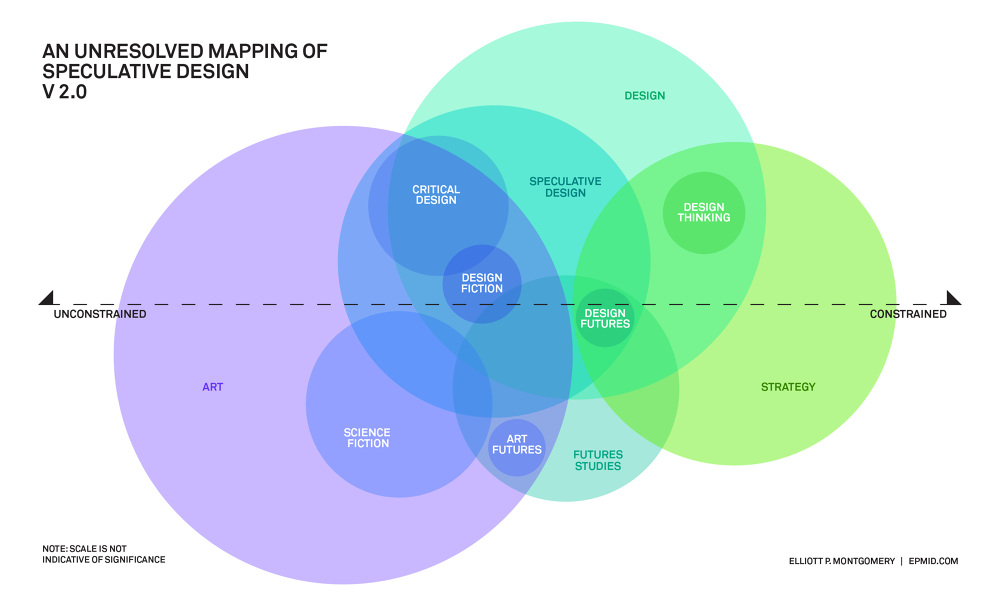

It’s always tricky to throw a definition around something. In 2020, trying to thrown one around the genre that was once speculative design is even trickier. There’s been a lot of different attempts which have themselves broadly fallen into two categories; impenetrable academic treatises that either add it to the interaction design toolkit or propel it into some philosophical netherworld or productivity hype, where it is appropriated into innovation cycles. Elliott Montgomery has done a pretty decent job of trying to map out the space around it, creating a map I’d broadly recognise.

What’s missing from Elliot’s map here is some dimensionality. That muddled space between ‘art’ and strategy is a deeper space where something that is a method, approach or tool that might broadly be applied across a range of fields as opposed an attitude or discipline. For example, ‘design fiction’ covers a huge range of cases; everything from advertising through to critical artistic practice. While something like critical design I would suggest is highly constrained as a discipline of critiquing design.

Equally therefore, not all design fiction is speculative design; some design fictions are not intended to speculate but to propose or cement an ambition of the future; think of product visions from Microsoft, they’re not asking a ‘what if?’ – they’re selling a vision. These works are formal design fictions in that they are designs that are fictional, but not necessarily speculative and very rarely critical. Similarly it’s difficult to think of an opposite – a speculative design that is not a design fiction.

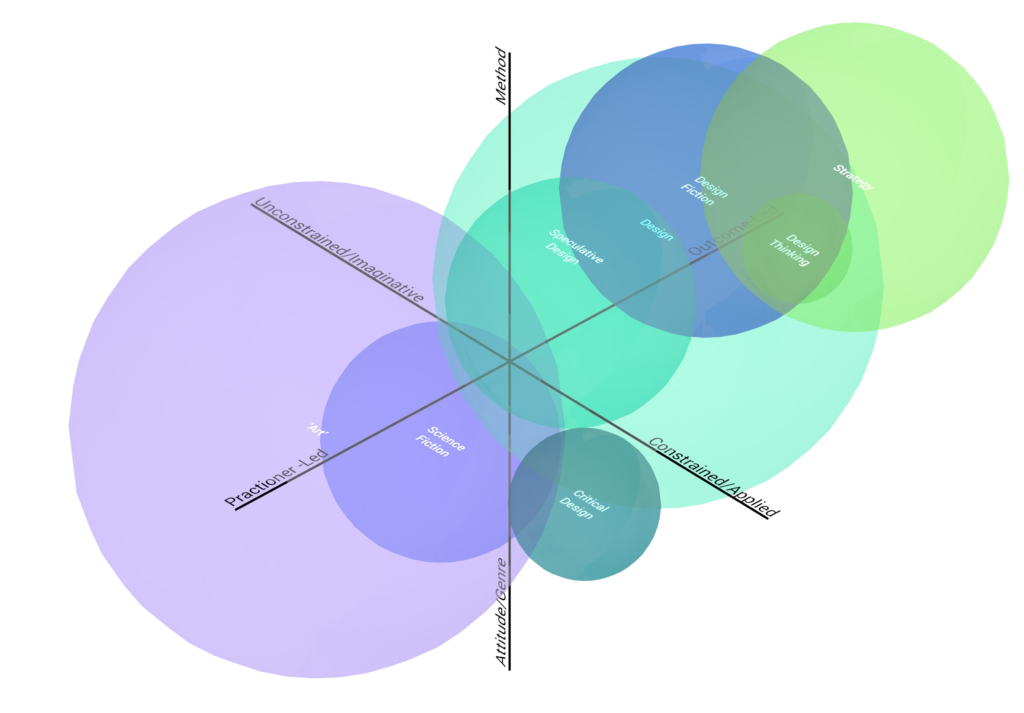

So, in writing this I decided to – with the deepest of respect – rework Elliott’s map a little. I’ve stuck to the original colour to try and show where I’ve moved things. I’d be quick to caution that many of these mapping exercises so revered by design academics are largely futile, highly subjective and broadly irrelevant to the actual experience of practice. Nonetheless, it’s something I’ve been meaning to do for a little while.

The axes definitions here are still work in progress. I want to demonstrate a couple of things. First of all, the relationship of the work to the creator. Here this is outcome-led versus practitioner-led to describe say a client-led project versus a more reflexive experiment that a practitioner might do out of their own interest. Secondly, I’ve reworked Elliott’s constrained/unconstrained with my own interpretation – applied/imaginative. This is similar to the first axes but is less about the intention of the practitioner in their own work than the way it is received or considered by others. So a client-focussed project might still be broadly theoretical in execution, while a personally reflexive project might be a very distinct, applied product. Finally is the axes I was hinting at earlier, the one that slides form method to attitude/genre (or discipline). Here, design fiction is up top as a method while science fiction and critical design slide down into the bottom.

Gadget Realism

All of this was a long way round of thinking about a brief discussion with Simone Rebaudengo via Instagram having consumed his new book of design fiction fairy tales Everything is Someone. It’s a short little book of allegorical stories about things. It’s packed with coded references to design fiction projects, not least the work of Automato.farm and Rebaudengo’s great Teacher of Algorithms. Stylistically it sits somewhere between a Tim Burton fairy tale book and some of China Mieville’s shorts. It’s not as out-there weird as China Mieville’s excellent collection of short stories Three Moments of an Explosion, though it did remind me of it for its focus on non-human things and it hints at surreal and magical narratives opened up by considering things as actors. So I decided to call it ‘gadget realism.’

Where ‘magic realism’ is the contextualisation of supernatural or magical phenomena in a mundane setting, reaching all the way from Borges to Mieville’s ‘new weird’ when a ‘highly detailed, realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe’ gadget realism examines, usually through design fiction, the weirdness of gadgets and their strange effects on the world, often centering them as characters. In magic realism, the ‘magic’ is usually outsize and off-screen, it influences the characters but rarely has fully explored motivations.

Keichi Matsuda’s Hyperreality springs to mind easily. Here the gadget (augmented reality) is initially normalised then the strangeness of it is revealed both diegetically and non-diegetically through the contradictory experience of us in our AR-absent world and the POV character who is experiencing non-AR in a deeply unsettling way.

In gadget realism, the gadget becomes a character that influences the world of the other characters, sending them on surreal journeys through its construction. If we can conceive of magic as a causeless technology then gadget realism would be a continuation of the same logic of a sort of ‘deus ex’ technology that influences the cause of events without displaying an apparent motivation. It’s important that the gadget must exceed the control of humans in the story in order that the strangeness be introduced. The Microsoft visions for example would not be gadget realism as they don’t provide the sublime, Lovecraftian experience of outsize influence over human life. In these design fictions, strangeness is avoided to recreate normalcy with believable gadgets.

There’s probably more work to do here exploring this sub genre. The reason I contextualise this in the mapping is to propose cutting across disciplinary and methodological boundaries for stylistic purposes. Gadget realism as a loosely formed notion seems to me to have the potential to ground and anchor outsize technologies in a narrative framework that understands them as more than utilitarian devices. For example, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s The Subsitute is not a design fiction or speculative design (I’d bracket it under critical technical practice) but is a form of gadget realism, exploring the outsize strangeness of machine learning.

Short stuff

That took me exactly too much time to do for what was supposed to be another brief missive. I have actual writing to do for actual things. Couple of quick ones:

- Arebyte have a browser exhibition called Real-Time Constraints. It’s a browser plugin. Every few hours an art pops up on your desktop. It’s a great format and there’s some great artists. Thanks Miranda Marcus for bringing this to my attention.

- This person restores old tools and gizmos. Each video is about twenty minutes, very mediative stuff. Why is that we love watching these processes so much?

I can’t think of a third one right now, I’d usually have a list. Anyway, love you, have a great week.